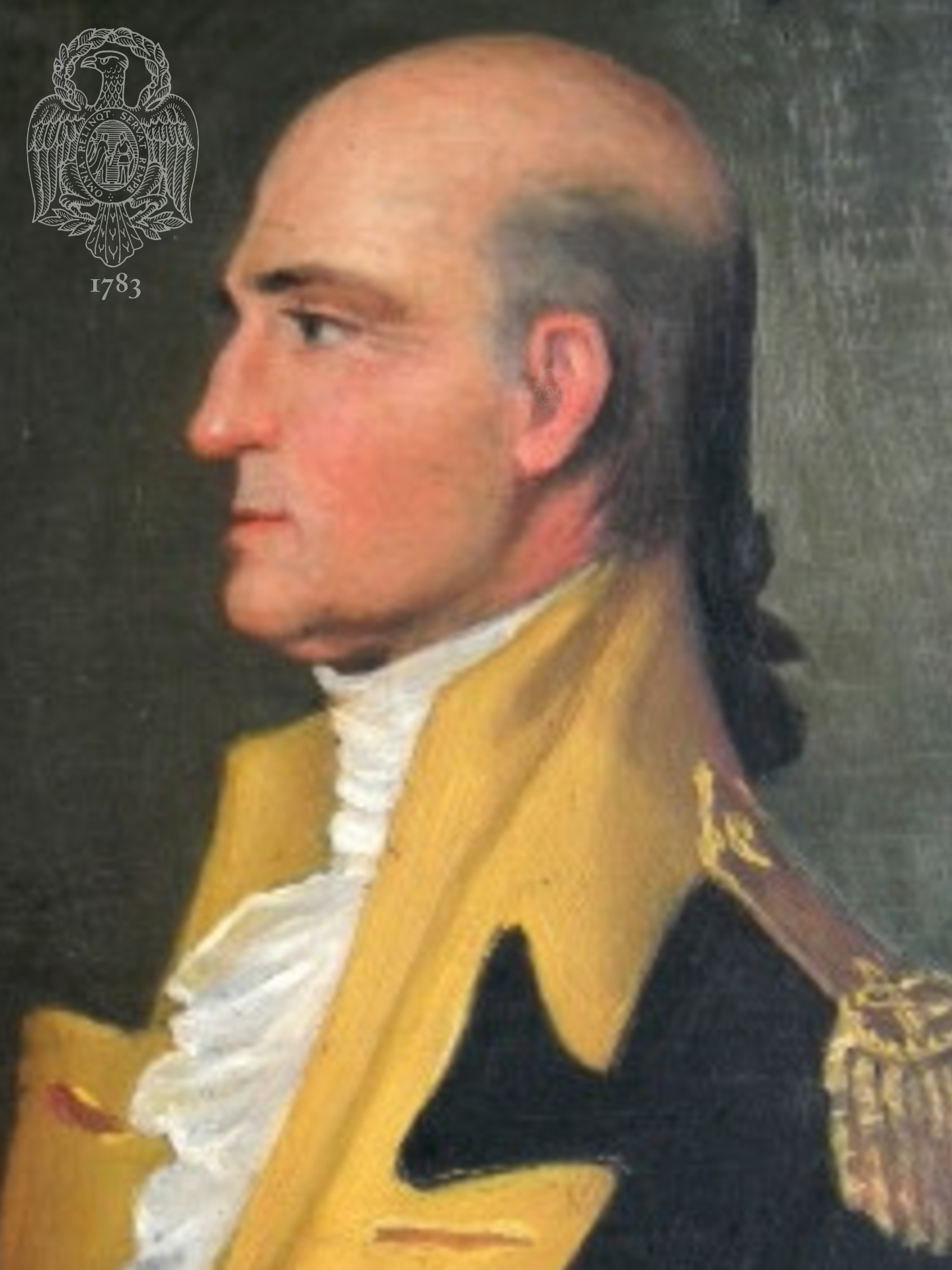

B. Gen. Edward Hand

Hand was born in Clyduff, Kings County, Province of Leinster, Ireland, on 31 December 1744, the son of John and Dorothy Hand. He studied medicine at Trinity College, Dublin, became a Surgeon’s Mate in the Eighteenth Royal Irish Regiment of Foot, and accompanied this regiment to America in 1767. Soon afterwards the regiment was ordered to garrison Fort Pitt, calculated to keep in check the French at Fort de Chartres in the Illinois country. In 1772 Hand purchased an Ensign’s commission in his regiment, an indication that he possessed sufficient financial resources, but the same year, on the withdrawal of the French on the Mississippi, the British government abandoned Fort Pitt and the regiment returned to Philadelphia. His service on the frontier, though as a subaltern, was so satisfactory that it was to impress his future superiors favorably: he was contantly to be utilized in Continental service at the edges of civilization, a stellar instance of Washington’s genius for realizing the potential qualities and talents of his men.

In 1774 Hand resigned his commission, removed to Lancaster, and prepared to enter medical practice in that town. That he was no stranger there, or in important eastern Pennsylvania social circles, is indicated by his marriage in 1775 to Katherine, the daughter of Captain John and Sarah (Yeates) Ewing. With this marriage Hand became allied to a widespread and influential lineage, which could have done nothing to hinder his future career.

At the outbreak of hostilities in 1775 Hand did not hesitate in his loyalties: on 25 June he was commissioned Lt Colonel of Colonel William Thompson’s Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion and on 1 March 1776 he replaced Thompson as commander. He remained in command when the regiment was designated the First Pennsylvania Regiment but relinquished that post on 1 April 1777 to James Chambers.

John B. B. Trussell makes this acute and important observation concerning Hand’s command of the First Regiment:

One point worthy of particular note is the difference between the February and April [1776] sick rates for Thompson’s Battalion….A factor which cannot be discounted,…is the change of command which took place on March 1, 1776. Edward Hand, who replaced William Thompson as colonel, was not only a physician but had served as a surgeon’s mate in the British Army. It seems possible that he introduced and, as commanding officer, enforced field hygiene procedures which were of direct benefit to the health of the battalion. This possibility is reinforced by the fact that this organization had significantly lower sick rates than the other units in New York, at least until after the Battle of Long Island, even though it was exposed to the same conditions of weather and climate.

Hand had commanded the First Regiment at the battle of Princeton on 3 January 1777, and family tradition reported that he there lost the sight of his right eye as a result of being wounded.

When Hand was appointed Brigadier General on 1 April 1777, turning over command of his regiment to his lieutenant colonel, it may already have been determined where he was next to be sent. The increased hostilities on the western borders of Pennsylvania caused the Continental Congress to strengthen Fort Pitt and place in command “an officer of experience”, but it was envisioned that the chief military force would be the local militia. Hand was selected for the command, money and armaments were ordered, and the new general arrived at Fort Pitt on 1 June. His command there was complicated not only by Native American hostilities, but because of the conflict between Pennsylvania and Virginia over jurisdiction. Hand’s projected retaliatory campaign against the Ohio tribes for the Fall of 1777 had to be abandoned, and by Christmas Hand wrote the Board of War asking to be recalled so that he could rejoin the Main Army. To Jasper Yeates he was more candid; “I am so heartily tired of this place that I have petitioned Congress to be recal’d”: a notable example of the frustrations experienced by the military “regular” when dealing with the “volunteer”, in this case the militia of Westmoreland County. It was a situation to be repeated in the cases of all his successors in this command.

Congress was not to be moved so swiftly as Hand hoped but there was plenty to occupy his energies. There is every evidence that he performed as efficiently as he could in his mission to militarize the frontier for defense. He had constantly to deal with reports of Tory plots. Still mindful of his medical training, as early as September 1777 the general dealt with an epidemic of small-pox and measles among his men by establishing a hospital on land on Chartiers Creek, acquired by him during his first tour of duty in the west. This has been called the first hospital west of the Susquehanna River.

Hand’s campaign against the British-Native American strongpoint at the present Sandusky, Ohio, got under way in February 1778 when he left Fort Pitt with several hundred militiamen. Inclement weather with consequent flooding prevented Hand’s reaching his objective, and he turned back with his recalcitrant men and two captured squaws. This unfortunately had the result of the sally’s being dubbed “The Squaw Campaign”. Hand was more successful in supplying George Rogers Clark’s Illinois campaign in May 1778. In March 1778, nearly at the end of his command in the west, Hand had the humiliation of having to report the escape of notorious Tories Alexander McKee, Matthew Elliot, Simon Girty and some others from prison at Fort Pitt. On 2 May Congress granted Hand’s request and recalled him. Washington transferred command at Pitt to General Lachlan McIntosh of Georgia, and on 6 August Hand wrote his wife that he expected to set out for Lancaster “the day after tomorrow.”

On 8 November 1778, Hand was put in command at Albany, New York, succeeding General John Stark. Perhaps coincidentally, Captain James Parr’s company from Hand’s old command, the First Regiment, was also on the New York frontier. The new posting indicates that Washington had not lost confidence in Hand however unsuccessful his efforts at Fort Pitt may have appeared.

Planning for a campaign against the Iroquois was already under way, and Hand’s frontier experience naturally recommended him as a participant. In the resulting Sullivan-Clinton Iroquois Expedition (May-November 1779) Edward Hand commanded the Third Brigade, composed of the Fourth and Eleventh Pennsylvania Regiments, the German Regiment, Proctor’s Artillery, Captain James Parr’s Riflemen, Captain Anthony Selin’s Riflemen, and two Wyoming companies. The brigade composed the “Light Corps” of Sullivan’s army and formed its van. The journals kept by the officers on the expedition indicate that Hand played a major role in the success of the campaign. When he rejoined his family in Lancaster at the close of the year he was thirty-five years old, the youngest of the brigadiers.

“Light Infantry” was a relatively new concept in the military science of revolutionary times. Such units were so called because they were “light” in armament and equipment, the better to help them fulfill a role as skirmishers. Washington had experimented with light companies from the beginning, and when the Continental Army was re-formed in May 1778 each infantry regiment had a light infantry company; Wayne, at least, dramatically showed their value and use at Stony Point in July 1779. Hand had further demonstrated their usefulness in the Sullivan’s campaign. In August 1780 a permanent brigade of light infantry was formed in the Army and Hand became its commander, but in January of the next year Washington selected Hand as Adjutant General of the Continental Army, in succession to Alexander Scammell. Hand was one of the fourteen generals who tried and condemned Major John André in September 1780 ; as Adjutant General he accompanied the army south to Yorktown and was present at the surrender. Hand continued as Adjutant General, was brevetted Major General on 30 September, and retired from the army on 3 November 1783 with a reputation as an excellent horseman, with skill in military science, and a strict disciplinarian.

When the Society of the Cincinnati was founded on the banks of the Hudson River on 10 May 1783, Hand was at Washington’s headquarters there, and he had the honor of being one of the signers, with Washington, of the great Parchment Roll of the General Society of the Cincinnati. At the disbanding of the Continental Army Hand returned to Philadelphia, and with his fellow officers signed also the Parchment Roll of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania, as well as the “Pay Order of 1784”. From 1799 to 1801 Hand was the President of the Pennsylvania Society.

Hand easily moved into private medical practice in Lancaster and acquired a reputation for charitable medical services to the poor. In 1785 he acquired a handsome estate which he called “Rock Ford” on the Conestoga near Lancaster. The census of 1790 for Pennsylvania shows Hand a resident of Lancaster Borough with two other males over sixteen years of age, two males under sixteen, and nine females.

Hand did not long remain in private life as he was elected a member of Continental Congress for the session 1784-1785, a member of the state legislature, 1785-1786, was a Presidential Elector in 1789, and the same year was Burgess of Lancaster Borough. He was a member of the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention of 1790. Like most of his fellow officers he was a Federalist, and in 1800 strenuously opposed Jefferson’s Republican ticket in Pennsylvania.

In 1791 Hand received a presidential appointment as Inspector of Revenue in the Department of Pennsylvania and held the office until 1801. Washington again called upon him in the crisis of the Whiskey Insurrection. As Adjutant General he again accompanied the army to Fort Pitt, his last visit there. During the Quasi-war with France in 1798 Hand was commissioned Major General in the United States Army and was honorably discharged therefrom 15 June 1800.

Like many other office holders who were opposed to Jeffersonian republicanism, General Hand found himself in trouble under the new administration. Required to settle his official accounts, he encountered difficulty in doing so, and in 1802 a petition, implicating him in defalcation, was brought into court to require him to sell his lands, notably “Rock Ford”. On 3 September 1803 the general died at “Rock Ford” from a stroke of apoplexy. He was buried in the churchyard of St. James Episcopal Church in Lancaster where he had been a churchwarden. He died intestate, and his affairs were in disarray. His wife Catherine (Ewing) Hand died 21 June 1805. There were eight children, among them three sons.