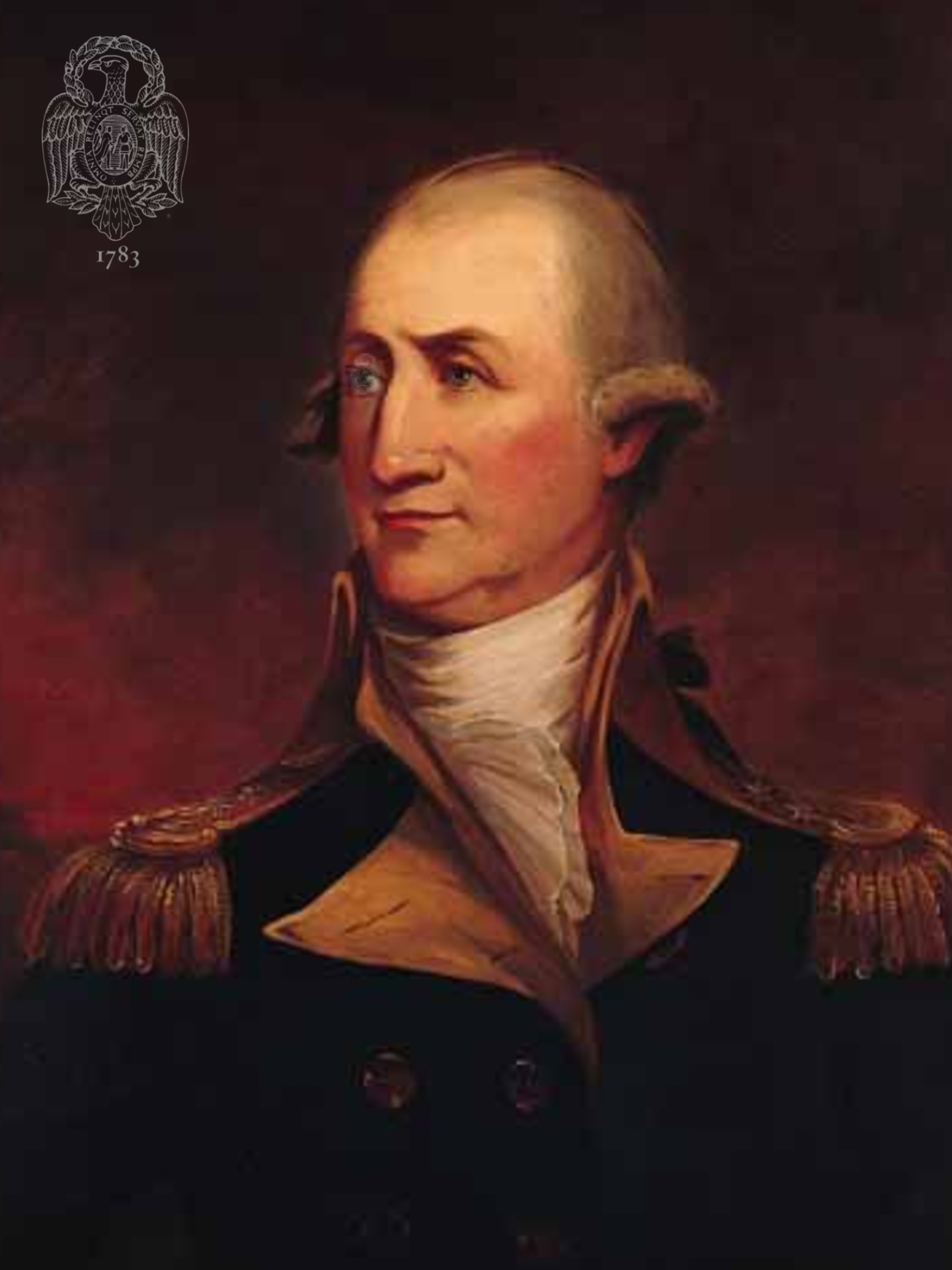

B. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg

John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg, because of his multinominalism often referred to simply as “Peter”, was born 1 October 1746 at New Providence (Trappe), Montgomery County, the eldest son of The Rev. Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711-1787) and his wife Anna Maria, daughter of John Conrad Weiser (1696-1760), famous in Pennsylvania’s Native American history. Because the father was such an important figure in the establishment of the German Lutheran church in America, the founder of a dynasty of Lutheran ministers and politicians, the family occupies a prominent place in the history of the Pennsylvania-Germans. Of the eleven children of the Rev. Mr. Muhlenberg seven reached maturity.

Peter Muhlenberg’s next brother, Frederick Augustus Conrad (1750-1801), was also a Lutheran clergyman but is more often remembered as a member of the Continental Congress in 1779 and 1780, a Republican (Federalist) member of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, 1780-1783, of which he was Speaker in 1780, member also of the Pennsylvania convention to ratify the Federal Constitution in 1787, Representative in the United States Congress 1789-1797 and Speaker of the House in the First and Third Congresses, President of the Pennsylvania Council of Censors in 1784, and Receiver General of the Pennsylvania Land Office 1800-1801. The third and last brother, Gotthilf Henry Ernest (1753-1815), a Lutheran clergyman, became the first president of Franklin College (now Franklin and Marshall College) in 1787, and was an early authority on American botany.

The eldest sister of these men was Eve Elizabeth, born in 1748, who married the Rev. Emanuel Shulze, a Lutheran clergyman at Tulpehocken; they were the parents of The Rev. John Andrew Melchior Schulze, better known as John Andrew Schulze (1775-1852), Governor of Pennsylvania from 1823 to 1829. Margaret Henrietta, the second daughter, born in 1751, married the Rev. John Christopher Kunze (1744-1807), founder of the German Department of the University of Pennsylvania and a professor of Oriental Languages at Columbia University. The youngest of all the children, Maria Salome who was born in 1766, married Matthias Richards (1758-1830) of Montgomery County, a soldier in the Berks County Militia (1777-1778) and Major of the Fourth Battalion of the Philadelphia County Militia in 1780. Mr. Richards held many Berks County offices and was a Representative in the United States Congress from 1807 to 1811.

John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg seems to have been miscast for a clergyman from the beginning, and it is likely that the career of his grandfather Conrad Weiser spoke to him more distinctly than did that of his father. His early years were spent at New Providence but in 1761 the family removed to Philadelphia. His education had not been neglected and in 1762 his father wrote,

…My eldest son, Peter, is entering his sixteenth year. I have had him taught to read and write German and English, and, after the necessary instruction, he has been confirmed in our Evangelical Church; moreover, since I have been in Philadelphia, I have sent him to the Academy to learn the rudimenta linguæ latinæ….

The next year Peter and his brothers Frederick and Gotthilf were sent by their father under the care of William Allen, Chief Justice of the Province then sailing for England, to Gotthilf August Francke, administrator of the Francke Foundation at Halle in Saxe-Anhalt, Germany. The boys were either to be educated for the Lutheran ministry or to be fitted for some other profession. Peter was apprenticed for six years to a grocer in Lubeck in an experiment that proved to be a complete failure. In 1766, nearing his majority and having suffered considerable abuse from his master, Muhlenberg absconded, enlisted as “Secretary to the Regiment” then enlisting at Lubeck for service in America, returned to Philadelphia on 15 January 1767, and was discharged from the military. It is evident that his father now did not know what to do with him; in March Mr. Muhlenberg wrote a clerical colleague in London that Peter was attending a private English school in Philadelphia where he was learning bookkeeping. It was proposed that he be a druggist, or a grocer, or a teacher among the Native Americans, who still respected the memory of his grandfather.

None of this came to pass. Whether because of his perceived failure in Europe, bravado on the father’s part, or a sincere “conversion” is not known, but Peter Muhlenberg was now put under the instruction of The Rev. Carl Magnus von Wrangel, provost of the Swedish Lutherans on the Delaware and a close friend of Peter’s father, and was put in charge of two of his father’s churches in New Jersey. The younger brothers came home from Europe and in the Fall of 1770 were ordained in the Lutheran ministry. But Peter on 6 November was married to Anna Barbara Meyer, daughter of a Philadelphia potter. He continued in charge of the New Jersey churches, but in May 1771 he was invited to become the Pastor of the Lutherans at Woodstock in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia where most of the settlers were from Pennsylvania. There was a condition, however: he must be willing to go to England and receive his ordination in the Church of England. This was not so strange as it may now appear, for the Church of England was then established in Virginia and only an Anglican minister could legally receive the tithes provided for his maintenance. Muhlenberg accepted the condition and on 2 March 1772 he sailed from Philadelphia, arriving at Dover on 10 April.

He was not without connections in London; he and his brothers had travelled to Halle via London in 1763; his father had lived and preached there in 1742 and still carried on a correspondence with Lutheran clergy attached to the Hanoverian Court in England. Peter’s arrival had no doubt been smoothly prepared and he was ordained Deacon by the Bishop of Ely on 21 April and Priest by the Bishop of London on 25 April; William White, afterwards the first Episcopalian Bishop of Pennsylvania, was ordained at the same time.. Muhlenberg passed his time in visiting John and Thomas Penn, Proprietors of Pennsylvania, and “seeing” the City. He sailed for Philadelphia on 24 May and, after a slower passage than the eastward one, was home by August. He removed to Virginia in September and became the pastor of his Lutheran church without ever having received Lutheran ordination.

In spite of all this, it is difficult not to think that Muhlenberg’s ecclesiastical career had now reached its peak. He was certainly the leader of the bilingual Lutheran community at Woodstock, but by 1774 his secular position was equally emphasized when he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses and was made Chairman of the local Committee of Public Safety. He was present in Richmond on 23 March 1775 for Patrick Henry’s speech ending, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death.” Muhlenberg there met George Washington, if he had not done so before this time, and there was probably for him then no turning back.

On 11 January 1776 the Virginia Assembly authorized raising the Eighth Virginia (“German”) Regiment, and on 12 January Muhlenberg accepted its colonelcy and the responsibility of raising the regiment in Virginia’s western counties. He was then twenty-nine years old, and his decision was not at all in accord with the ideas of his clerical family. There is the often-told tale of Muhlenberg’s ascending his pulpit at Woodstock for the last time, probably in January, and ending his sermon with some such words as, “There was a time to fight, and that time has now come!” Removing his clerical gown, Muhlenberg then revealed that he was wearing his military uniform. Whatever it was that Muhlenberg did, it must have been dramatic for the tale has long been remembered.

Enlistments in his regiment were for but one year, and its story belongs to Virginia’s military history. It was the first Virginia regiment to serve outside the state, and was present at Charleston in June 1776, afterwards at Savannah. Early in 1777 the regiment was reorganized under Colonel Abraham Bowman, and Muhlenberg on 21 February was commissioned Brigadier General.

Muhlenberg commanded brigades at Brandywine on 11 September 1777 and at Germantown on 4 October, with credit in both engagements. In December, preparing for Valley Forge, Muhlenberg’s Brigade consisted of the First, Fifth, Ninth and Twelfth Virginia Regiments, the Maryland-Pennsylvania German Regiment, and the Virginia State Regiment. It is evident that Washington wanted Muhlenberg’s command to be primarily of Virginia troops. At Valley Forge Muhlenberg took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States on 12 May 1778, witnessed by George Washington. His brigade, in Nathanael Greene’s command, was present at Monmouth on 28 June 1778. Muhlenberg wrote his brother-in-law Schulze on 28 July from White Plains,

…the particulars of the Battle of Monmouth you have had over and over again however I shall only tell You, it was tho’ a Glorious day, very distressing times, We fought in a Sandy barren, on one of the hottest days ever known in this part of the World, and where neither Money[,] Authority, or favor could procure a drink of Water…I had little Share of the Action, I commanded the two first Virginia Brigades, in the Second Line or Corps de Reserve, it was indeed a disagreeable post to me, as we were Oblig’d to Stand within Sight of the enemy, where they Cannonaded us Severely, while we Stood patiently without returning the Compliment, waiting when we should be order’d to Attack, however they saved us the trouble by running away before it came to our turn,…

By September the brigade had been moved to the vicinity of West Point; the reorganization of the Army that had then taken place replaced or renamed some of his regiments, but they were still Virginia troops. In November Muhlenberg was at Fort Clinton on the Hudson in command of the Division of General Israel Putnam, who not long afterwards resigned because of a paralytic stroke.

By July 1779 Muhlenberg’s Brigade was somewhat differently composed: it consisted of the First, Sixth, and Tenth Virginia Regiments, the First and Second Virginia State Regiments, and Gist’s Additional Regiment all Southern units. At Stony Point on 16 July 1779 Muhlenberg commanded a reserve force of three hundred men, but was not engaged. Anthony Wayne reported to Washington on 17 July,

I forgot to mention to your Excellency, that previous to my marching, I had drawn General Muhlenberg into my rear, who, with three hundred men of his brigade, took post on the opposite side of the marsh so as to be in readiness either to support me, or to cover a retreat in case of accident, and I have no doubt of his faithfully and effectually executing either, had there been any occasion for him.

It has been stated that Muhlenberg was sent to Virginia to take command of the Continental troops there, but the facts seem to be that he started for Virginia on a leave of absence but was delayed in Philadelphia because of the fierce, inclement weather of the Winter of 1779-1780. While there he received orders from the Board of War in February to take charge of recruiting in Virginia; Henry Clinton was besieging Charleston, and it was obvious that if he succeeded there his attention would then turn to Virginia. Charleston fell on 12 May 1780, with the loss of an American army. Muhlenberg’s prime responsibility then became the mustering of Virginia’s military forces, chiefly under the command of Steuben, who came south with Nathanael Greene after Gates’ defeat at Camden on 16 August. It was obvious then that any support for Greene’s command, whether of men or supplies, must come from Virginia. Muhlenberg’s duties required carefully balancing the egos of Washington, Steuben (perceived as arrogant), and Jefferson (perceived as reluctant).

By January 1781 Steuben, Muhlenberg, and the Virginians George Weedon and Thomas Nelson had mustered a sizeable Virginia militia to oppose a three-fold led by British Generals Alexander Leslie, Benedict Arnold and William Phillips. On 5 January Arnold entered and plundered Richmond, sending Governor Jefferson scurrying for the Albemarle hills. The untrained militia obviously needed stiffening, and Washington sent Lafayette to Virginia with twelve hundred Continentals, to be supplemented by Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvanians and a French naval force from Rhode Island under the Chevalier Destouches. Destouches never arrived, being intercepted by the British Navy on 16 March. Lafayette started from Baltimore on 19 April and arrived at Richmond on the twenty-ninth. On 7 May Cornwallis started for Virginia. Lafayette with about two thousand militia, one thousand light infantry, and forty men of Armand’s Legion, opposed Cornwallis’ army of forty-five hundred regulars. Lafayette wrote, “I am not strong enough even to get beaten.” Cornwallis wrote, “The boy cannot escape me.” On 10 June Anthony Wayne’s force finally joined Lafayette – with but one thousand men.

The details of the ensuing Yorktown Campaign have been given many times. General Muhlenberg there commanded the First Brigade of Lafayette’s Light Infantry Division, composed of three battalions of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and New Jersey men, about seven hundred in all. The Chevalier de Gimat’s Second Battalion of his command was in the van of the assault on Redoubt Number Ten on 14 October; Cornwallis’ surrender occurred on the nineteenth.

On 23 October 1781 Muhlenberg asked Washington’s permission to go to his family at Woodstock to recover his health because of “A Constant & violent fever I have had for Ten days past…”. Permission was given and Muhlenberg went into seclusion in his Virginia mountains. The war, of course, was not yet over and in March 1782 Muhlenberg received orders from Edward Hand [an Original Member of the Society], Washington’s Adjutant General, to remain in Virginia on recruiting duty. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 5 September 1783, and on 30 September Muhlenberg was given the brevet rank of Major General and he retired from the service on 3 November. The same month that he left the Army he also left the Lutheran ministry and the Commonwealth of Virginia, and returned to Pennsylvania.

Muhlenberg’s personal affairs resulted in a rather curious relationship with the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, organized at Fredericksburg on 6 October 1783. As a senior officer of the Virginia Line Muhlenberg issued the call for the meeting, but when it convened General George Weeden, President pro tem., “laid before the Board, a Letter from Brigadier General Muhlenberg acquainting them of his illness and inability to attend the Meeting;…”. On 8 October “…the Secretary having prepared the Papers directed in the proceedings yesterday, the several officers proceeded to subscribe their respective names and rank,… Ordered, That the Subscription Roll lie open for such Officers entitled to become Members.” In the severely damaged “signature roll”, now in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, “P. Muhlenburg B.G. [served] From Jan 7 1776 to Oct 1783 Residence Shanandoah” appears just after Horatio Gates’ and George Weeden’s names. But the evidence is very clear that Muhlenberg was not at this meeting (or any other meeting of the Virginia Society), that his misspelled name is not in his handwriting, and that there is other evidence showing that the names of missing members were entered by the Secretary, probably Oliver Towles. The officers completed their organization on 9 October by electing Horatio Gates President, and Muhlenberg Vice President of the Virginia Society.

Peter Muhlenberg’s name also appears in the surviving account book of the Treasurer of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, opened on 4 July 1784, when he was debtor in the total amount of £38.14.0, for his subscription and for an assessed contribution for the contingent fund of the Society. As late as 1 June 1802 Muhlenberg was still carried as delinquent in the Virginia Society. Similarly, Muhlenberg’s name occurs in a report submitted to the Pennsylvania Society on 20 July 1789 by a committee appointed “to apply to such Members of the Society who have not paid their subscriptions, for the Immediate payment thereof.” This appears to have had its effect, for in an undated roster of the Pennsylvania Society, probably compiled shortly after 1789, Muhlenberg is shown to have furnished a funded certificate in the amount of $125. Muhlenberg served on the Standing Committee of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania in 1788 and 1789, but held no other office.

When Muhlenberg left Virginia he possessed a Land Bounty warrant for twelve thousand acres “in consideration of his services for seven years as a Brigadier General in the Virginia Continental Line.” He also had a brief from Steuben and other officers to see to their bounty lands, and Virginia had appointed him to locate the tracts reserved for her soldiers. On 22 February 1784 Muhlenberg set off for the Ohio via Carlisle, where he acquired Captain Frederick Paschke [an Original Member of the Society] as a travelling companion. They arrived at Fort Pitt on 10 March, acquired a flatboat named Muhlenberg, and set off for the Falls of the Ohio, now Louisville, Kentucky. His survey was inconclusive and in some ways unsatisfactory, and it certainly changed his mind about settling in the West. Kentucky honored Muhlenberg anyway by giving his name to a southwestern county.

Perhaps encouraged by the political successes of his brother Frederick, Muhlenberg now plunged into the dizzying ferment that characterized Pennsylvania politics in the post-war era. It was a period of party formation, succeeding an era in which the concept of “party” was considered as divisive, if not subversive, among a people previously united against the ministerial politics of 1760 to 1780. Emerging Americans were not yet sure where to deposit their political allegiances. Muhlenberg is, in fact, a good case in point: coming to Pennsylvania politics as at least a nominal Republican (anti-Constitution of 1776, Federalist), he ended his career as a Jeffersonian Republican (Anti-Federalist). His history thus is in contrast to that of most of his fellow officers who tended to be conservative Federalists. In Muhlenberg’s case there was a further complicating factor: he was looked upon as their hero and advocate by most Pennsylvania Germans, hitherto an overlooked and rather a passive element in a state where they composed about a third of the population.

A paragraph, taken out of context to be sure, from a study of Pennsylvania politics of the period serves to illustrate these comments:

The important political activity of the fall of 1788 centered in the choice of senators and representatives for the new Congress. Taking no chances on the composition of the next assembly, the expiring session in September chose the two senators. Long before this session convened on September 2, George Clymer and William Maclay had been talked of for the posts, but political winds shifted quickly. A number of citizens waited on Robert Morris and received his consent to serve; thereupon he and John Armstrong, Jr. [an Original Member of the Society], were considered the logical candidates. The Anti-Federalist forces considered their old standard bearer, [Benjamin] Franklin, whom they planned to team with the moderate William Irvine [an Original Member of the Society]; but there were drawbacks to this plan. Some even thought of taking up Maclay who was feeling bitter at being dropped by the Republicans. When it was pointed out that Irvine had been appointed by Congress to settle accounts in the Treasury Department, James McLene considered it as “A scheme hatched” to put Irvine out of the running. In the ensuing two and a half weeks developments occurred so that the day before election the Republicans discovered that Armstrong could muster only seven out of thirty-three votes. Armstrong’s youth and inexperience in public life were handicaps and the Republicans turned to their original choice of William Maclay. On the morning of the election Armstrong and [Peter] Muhlenberg were withdrawn by their respective parties, and the ballots showed sixty-six votes for Maclay, thirty-seven for Morris, and thirty-one for the luckless Irvine. Irvine’s friends reported that the Maclay clique arranged at the last moment to freeze him out. Thus Morris and Maclay became the first senators to Congress from Pennsylvania.

Speaking of the Pennsylvania elections of 1799 one writer summed up very well the political situation and Muhlenberg’s place therein: “…one must not ignore the support of Peter Muhlenberg, who enjoyed a great popularity in the [Pennsylvania German] area that contributed most to [Thomas] McKean’s success [in the gubernatorial election]. His name on the Republican circulars must have meant a great deal to many who floundered about in a welter of misleading slogans, sophistries, charges and counter charges.”

Muhlenberg’s first political success came when he was elected to the Supreme Executive Council of the state in 1784, and he was its Vice-President from 1785 to 1787 under Benjamin Franklin. He was elected to the First U.S. Congress (1789-1791) and to the Third Congress (1793-1795), at which times his brother Frederick was Speaker of the House, where Peter was noted as never having made a speech. It might also be noted that the brothers belonged to opposing political parties. Peter was a Presidential Elector in 1796 and was elected to the Sixth Congress (1799-1801). He then was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate, but served only from March to June 1801, when he resigned and was appointed Supervisor of Revenue in Pennsylvania by Thomas Jefferson. (Muhlenberg had voted consistently for Jefferson on all thirty-six ballots cast in the Jefferson-Burr election deadlock of 1801). He was made Collector of Customs at Philadelphia in January 1802 and retained the office until his death.

Anna Maria, the wife of General Muhlenberg died 27 October 1804 and was buried with the family at Augustus Church, New Providence (Trappe), Montgomery County. Peter Muhlenberg did not long survive her, dying at Gray’s Ferry on 1 October 1807; he was also buried at Trappe. There were six children of this marriage, the eldest being Henry Myers Muhlenberg who was born 9 October 1775 and died, leaving no issue, on 7 July 1806. His father, writing in 1799, said his son was then a Senior Lieutenant in the Corps of Artillery. The second son, Charles Frederick died underage and without issue. Peter Muhlenberg (1787-1844), the third son and fourth child married Sarah Coleman of Reading and left issue, but the two younger children left no issue. General Muhlenberg is commemorated by statues in City Hall Plaza, Philadelphia, and in the Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol.