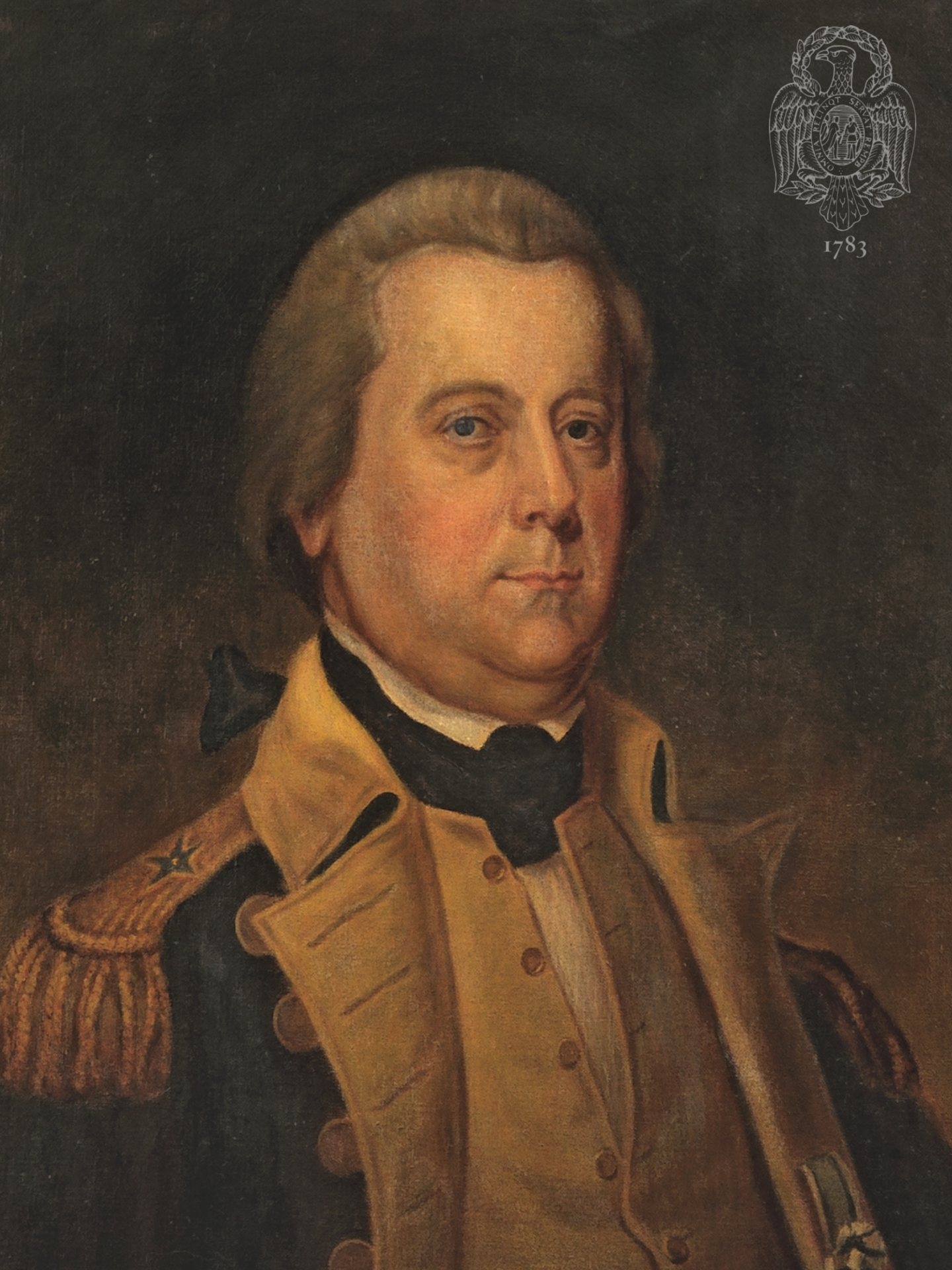

B. Gen. William Irvine

William Irvine, born 3 November 1741, was one three brothers of Inniskillen, County Fermanagh, Ulster, who came to this country as young men and later held commissions in the Continental Army. The others were Captain Andrew Irvine [an Original Member of the Society], and Surgeon’s Mate Matthew Irvine of Thompson’s Rifle Battalion and “Lee’s Legion”, who removed to Charleston, South Carolina, died in 1827, and did not become a member of the Society of the Cincinnati.

It has uniformly been stated that William Irvine studied medicine at Trinity College, Dublin, but inquiries of the Registrar thereof have brought the response that there is no record of his having matriculated. There is no doubt, however, of Irvine’s having medical qualifications and the further statement that he was a student of Dr. George Cleghorn is probably the basis for the error. Cleghorn undoubtedly lectured on anatomy at Dublin from 1751 to 1789, and Irvine was no doubt a private student or apprentice who did not receive the formal qualifications that university matriculation would have carried. The Dictionary of American Biography says “After a brief and unfortunate career at arms,…He was appointed surgeon on a British ship of war and served in the Seven Years’ War” [called the French and Indian War in America]. Certainly there was a William Irvine carried as a surgeon in the British Twelfth Dragoons from 19 May 1759 to 6 August 1760, but at that time Irvine would have been but eighteen years old.

Irvine probably emigrated about 1763, for by 1764 he was practicing medicine at Carlisle, Cumberland County. Although his manner was said to have been reserved and private, his practice was a flourishing one when the difficulties between Britain and America became unmanageable. In July 1774 he was a member from Cumberland County of the Provincial Convention in Philadelphia “held for the purpose of instructing the Assembly on the will of the people” as to the necessity for convening a “Continental Congress”. On 4 January 1776 the Sixth Pennsylvania Battalion was authorized to be raised in Cumberland and York Counties, with Irvine its Colonel. The history of the battalion and its fate in Canada have been recounted: on 9 June 1776 Irvine was captured at Three Rivers and, although soon released on parole, was not exchanged until 6 May 1778. The enlistments of the Sixth Battalion expired at the end of 1776, but it did not return to Carlisle until March 1777, to be succeeded by the Seventh Pennsylvania Regiment, of which Irvine continued to be colonel, even while still a prisoner on parole. His regiment wintered at Valley Forge in 1777-1778, and there Irvine took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States on 12 May 1778.

Irvine’s first action after resuming command of his regiment was at Monmouth on 28 June 1778. The Seventh Regiment’s only casualty was Sergeant John Hays, detached to serve with the artillery. Hays’ wife Mary (Ludwig) Hays had been an Irvine family servant, and it was about her that the “Molly Pitcher” legend grew. The Seventh remained in northern New Jersey that year, and wintered at Middlebrook during 1778-1779, but by the time some of its men were engaged at Stony Point on 16 July Irvine was no longer its commander, having been promoted to Brigadier General on 12 May, soon after his exchange. He sat on the Court Martial of General Charles Lee in July 1778.

Irvine’s commanded the Second Brigade of the Pennsylvania Line which remained active in New Jersey, being engaged at Staten Island on 14-15 January and at Bull’s Ferry on 20-21 July 1780, neither a success for the Americans. On 24 September 1781 Irvine was made commander of the Western Department and took command at Fort Pitt, succeeding Daniel Brodhead [an Original Member of the Society]. From a multitude of causes military and civil affairs in western Pennsylvania were in a deplorable case. Irvine merits being given credit for restoring a measure of accountability and responsibility in an area still in constant danger from Indian-British raids. It was misfortunate that the first of a series of American disasters, the defeat of the Crawford Expedition against Sandusky, May and June 1782, occurred at this time. The operation was carefully planned, and it was professionally commanded by Colonel William Crawford and Dr. John Knight, both of the Virginia Line, assisted by Lt. John Rose [an Original Member of the Society], Irvine’s aide, but the loose and undisciplined militia of which the “army” was composed was doomed when pitted against the Northwest Native Americans and their British allies. The Americans were utterly defeated and Crawford was captured and tortured to death.

Irvine remained in command at Fort Pitt until the close of the war and left for the east in October 1783. When the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania was organized in November he signed their “Parchment Roll”; he was the first Treasurer of the Society, 1783-1785, and President from 1801 to 1805. In 1783 also he was elected a member of the “Council of Censors” under the Constitution of 1776. Arthur St. Clair and Anthony Wayne were also on the Council.

Pennsylvania rewarded Irvine’s military services with a generous grant of land which formed the nucleus of the very large land-holdings of the family in present-day Warren, Venango and other northwestern counties. In 1784 the state made the “Last Purchase” of lands within its boundaries from the Six Nations. The purchase comprised most of northwestern Pennsylvania and from it the “Donation Lands” and the “Depreciation Lands” were carved. Irvine explored the region in 1785 and was later appointed agent for directing the distribution of these lands to the state’s revolutionary veterans. Becoming convinced of the necessity of Pennsylvania’s having a port on Lake Erie, Irvine advocated policies that resulted in the purchase of the “Erie Triangle” of more than 200,000 acres from the Federal government in 1792.

From 1786 to 1788 Irvine represented the state in the Continental Congress. He was a member of the Pennsylvania convention for ratifying the Federal Constitution in 1787, and in 1789 was a delegate to the convention which drew up Pennsylvania’s own new constitution of 1790, and from that date he was intimately involved in the convoluted history characterizing Pennsylvania’s transition to party politics. In 1793 Irvine served as one of the commissioners to settle the financial accounts between the several states and the federal government, and in the same year he was elected a Representative from Cumberland County to the Third United States Congress, serving one term.

In the summer of 1794 Irvine was in western Pennsylvania with Andrew Ellicott and others, ready to begin surveying at Presque Isle. The times were then tense and dangerous: Anthony Wayne was preparing the expedition against the northwest tribes that eventuated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers on 20 August, but Native American unrest was not confined to the Ohio region: the Six Nations in New York and Canada were also restless. It was not certain what part the British were playing. They were still in control of the frontier forts and it was known that their agents, notably the renegade Pennsylvanians John Connolly and Alexander McKee, were in the Ohio Valley awaiting opportunities to unsettle further any discontented American settlers. The Erie Triangle occupied strategic ground between the Native American nations and, even more important to the British, it dominated communications between Detroit and Fort Niagara. To Washington and Hamilton the situation was pregnant with international dangers and they insisted that Pennsylvania delay offering any opportunities for British and Native American hostilities such as might have resulted from opening the Triangle to settlers. To Governor Mifflin and Irvine, representative of Pennsylvania’s land speculators, the delay meant monetary loss but the issue brought forward for debate was the right of the Federal Government to interfere in a matter Pennsylvania preferred to think of as solely an internal matter. When Mifflin called a special session of the General Assembly in September he succinctly stated the question: whether “the interest of the Union, requires in any degree, a sacrifice of the local interests of the State…”. The matter may help explain Irvine’s abandoning the Federalists in favor of Pennsylvania’s Jeffersonians.

The issue of Presque Isle had, however, been overtaken by events: while Governor Mifflin waited for decisions to be made and for the determination of national policy, news of the attack on Colonel John Neville’s [an Original Member of the Society] house in July 1794 and the commencement of the “Whiskey Rebellion” announced a new crisis. An attempt was made at mediation and in August Irvine was sent with Thomas McKean, Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, to represent the Commonwealth in failed talks with the rebels. When military force was decided on in September Irvine commanded the Pennsylvania Militia with the rank of Major General.

At that time boundaries of Pennsylvania’s political factions were far from absolute: many identical names appear on what to Twentieth Century eyes seem to have been opposing “tickets”. Irvine’s political sentiments seem to have undergone a gradual change, from the general “Federalism” shared by Pennsylvania officers, to the opposition “Republicanism”. In this, Irvine may have been influenced by the “ultra liberal” or “radical” politics of the state’s frontier counties, of which Cumberland was one. As early as the elections of 1788 Irvine’s political loyalties may have been met with skepticism by his Federalists because of a quarrel with Robert Morris whom Irvine charged with having mishandled public monies. In 1796 Irvine was one of the Republican presidential electors that gave the State to Jefferson and was by then generally identified with the Jeffersonian party. In the elections of 1799, however, Irvine’s political stance was so ambivalent that he was no longer considered as of the inner circle of the state’s Republican party, although he had been mentioned as a possible successor to Governor Mifflin.

By contrast, when Irvine moved from Carlisle to Philadelphia at about this time, he was rewarded by the Jefferson administration in being made Superintendent of Military Stores, thus putting him in charge of arsenals and ordnance, and the supervision of Native American affairs. General Irvine continued to hold this post until his death “at his home on South 8th Street, Philadelphia,” which occurred on 29 July 1804. He was immediately succeeded as Superintendent by his son Callender Irvine.

William Irvine was married at Carlisle to Ann, daughter of Robert and Mary (Scull) Callender. Callender was an early, successful and influential Indian trader at Carlisle and by the marriage Irvine became the brother-in-law of Dr. John Andrews (1746-1813), Provost of the College of Philadelphia, and of Thomas Duncan, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1811. Mrs. Irvine outlived her husband by nearly twenty years and died in Philadelphia on 15 October 1823; both were buried in the cemetery of the First Presbyterian Church on Market Street. General and Mrs. Irvine had eleven children, of whom two died in infancy. Four of the sons, Callender (born 1775). William Neill (born 1782), Armstrong (born 1792), and James (born 1796) followed their father’s example by serving in the United States Army in the early Federal period. A street in Pittsburgh and the town of Irvine on the Allegheny River in Warren County memorialize the general and his family.