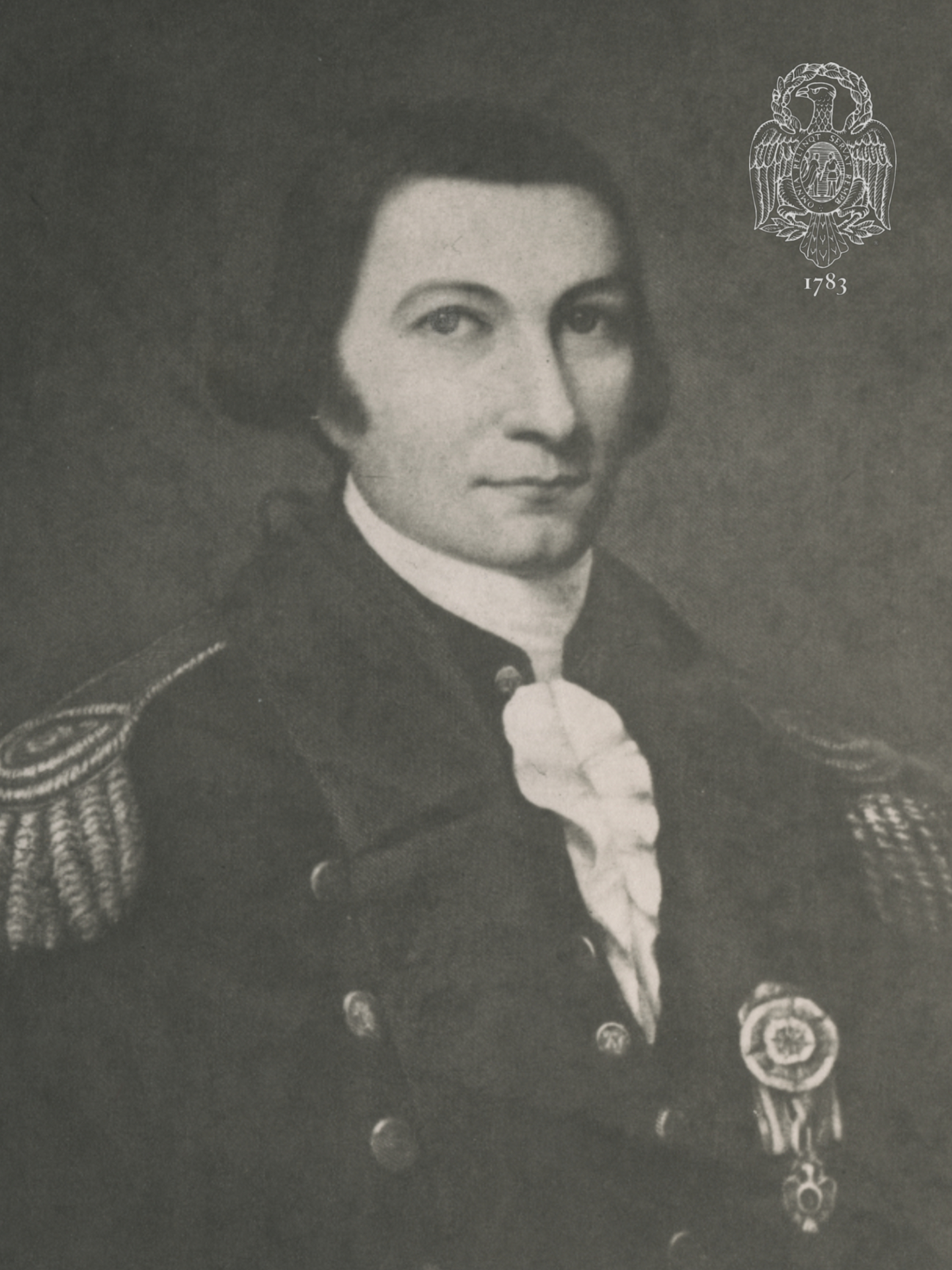

Capt. James Nicholson, Continental Navy

James Nicholson was born in or near Chestertown, Kent County, Maryland about 1736, one of the younger sons in the remarkable family of Colonel Joseph Nicholson and his first wife Hannah (Smith) Scott. Two of James’ brothers, Samuel (1743-1811) and John, were also Captains in the Continental Navy. The Nicholson family was large, influential, and had extensive connections not only on the Eastern Shore of Maryland but throughout the northern and central parts of that state. Through his mother’s family James Nicholson was connected with Captain Lambert Wickes and his brother Lieutenant Richard Wickes of the Continental Navy. Lieutenant Alexander Murray [an Original Member of the Society] of the Continental Navy and the Continental Army was also from Kent County, and served with Captain Nicholson.

Nicholson, like many of his fellow Eastern-Shoremen, went to sea when quite a young man. He is said to have been present, in what capacity has not been discovered, at the British siege and capture of Havana in 1762. Returning, he lived for a while in New York where on 30 April 1763 he married Frances, the daughter of Thomas and Mary (Lewis) Witter of Bermunda, but he returned to Kent County and was a resident there in 1775 when given command of the chief vessel of the Maryland Navy, the ship Defence. Nicholson operated well against hostile shipping in the Chesapeake Bay, but the Defense proved impracticable for the Maryland Navy and was soon sold at Philadelphia.

On 6 June 1776 Nicholson was commissioned Captain in the Continental Navy. When naval ranks were later established he headed the list of Captains, and when Esek Hopkins of Rhode Island was dismissed the service in January 1778, Nicholson became the senior officer and retaining that distinction for the remainder of his service. Initially, however, there was no command for Nicholson, and he and his crew were present at the Battle of Trenton on 26 December 1776 as landsmen. Nicholson’s first Continental command was the Virginia, built at Baltimore and ready for sea early in 1777, but the British blockade of the Bay kept her from sailing, with consequent desertions and difficulty in enlisting. Nicholson’s efforts to overcome these problems antagonized Maryland and Congress:

In Congress 29th April 1777.

A Letter of 26 from Governor Johnson of Maryland, inclosing a copy of a letter from the said governor to James Nicholson captain of the Virginia[,] and of Captain Nicholson’s answer being received, was read….

Resolved, That the said [marine] committee be directed to order capt Nicholson to dismiss all the men he hath impressed, and not to depart with the frigate till farther orders.

Nicholson’s ill-considered actions in impressing Maryland’s citizens and his cavalier attitude to Governor Johnson resulted in Congress’ resolving,

That capt James Nicholson be suspended from all command in the service of the United States, until he shall have made such satisfaction as shall be accepted by the executive powers of the State of Maryland for the disrespectful and contemptuous letter written by him to the governor of that state….

These difficulties were resolved and on 30 March 1778 in an effort to run the blockade Nicholson sailed the Virginia from Annapolis against the advice of the Maryland Council of Safety. Early the next morning his ship ran aground on a shoal, lost her rudder, and was discovered by two British frigates. Nicholson abandoned his ship to the enemy, leaving his Lieutenant, Joshua Barney, [an Original Member of the Society] in command. Nicholson was acquitted of negligence by a court of inquiry.

In the light of this it is not surprising that Nicholson did not obtain another command until September 1779, when he was given Trumbull by the Board of Admiralty. The frigate had been launched in 1776, but had ever since been found too heavy to clear a bar in the Connecticut River where she had been built. The difficulty was finally overcome, Trumbull was towed to New London to be fitted-out, and she was eventually ordered to sea in May 1780. On 1 June Trumbull fell in with the British letter-of-marque Watt, thirty-six guns. After one of the most hotly contested sea battles of the war, both vessels were badly damaged and withdrew. Nicholson was congratulated by the Board of War for his action. Although it had been intended for Trumbull to act in consort with Admiral de Ternay’s French fleet, the latter was effectively bottled up in Newport by the the British Admiral Arbuthnot. Trumbull and Deane, commanded by Nicholson’s brother, Captain Samuel Nicholson, sailed to Philadelphia and there was little employment for them for the rest of the year. Early in 1781, however, James Nicholson had the honor of commanding the fleet of small vessels that ferried Lafayette’s little army from Head of Elk to Annapolis, the first step in closing the trap at Yorktown.

Trumbull, which all this time had been outfitting in Philadelphia, sailed in convoy on 8 August for Havana with a crew of British deserters, recruited at Nicholson’s own suggestion. That night Trumbull lost her foretopmast and had to leave the convoy in sight of British ships, one of which was the thirty-two gun frigate Iris, the former American Hancock, captured and renamed. Nicholson called his crew of deserters to quarters, but later reported,

Instead of coming, three quarters of them ran below, put out the lights, matches, &c. With the remainder and a few brave officers we commenced an action with the [I]ris for one hour and thirty-five minutes, at the end of which the other ship [General Monk] came up and fire[d] into us. Seeing no prospect of escaping in this unequal contest, I struck [the colors],…My crew consisted of 180 men, 45 of whom were taken out of the new goal – prisoners of war; they through treachery and others from cowardice betrayed me, or at least prevented my making the resistance I would have done. At no time of the engagement had I more than 40 men upon deck.

Hancock was towed to New York where she was left to rot; the officers and men were prisoners of war. In spite of statements that Nicholson was sent to England as a prisoner, remaining there until the close of the war, he must have been quickly exchanged or paroled as he requested of Robert Morris a court of inquiry on 17 November. The court, convened on 30 November, consisted of Major Samuel Nicholas [an Original Member of the Society], James Craig and Nathaniel Falconer. Nicholson was found to have acted with honor in surrendering Trumbull.

On 13 March 1783, the war virtually over, Nicholson wrote the Supreme Executive Council,

Cap. James Nicholson of the Continental Navy begs leave to make Application to the Govr & Council of the State, for Permission for himself & Daughter to go into New York in order to have an Interview with his Father in Law, who Writes pressingly to that purpose.

In May Nicholson was ordered by Morris to return to New York to oversee the assembly of the transports by which the Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware troops were ferried home from Charleston. The fleet was chartered from Daniel Parker and Company, later to figure importantly in the China Trade. This was apparently Nicholson’s last official act as a naval officer although as late as 1785 he asked Congress’ permission to go to sea as captain of a merchantman.

Nicholson was in Philadelphia in the Fall of 1783 when he signed the “Parchment Roll” of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania, although in the “Report of Sub-Committee June 20th 1789” his name appears in the “List of Officers that Signed, but did not pay”. However, by 1785 he was a resident of New York City and in 1788 the Minutes of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati show, “…On the 4th July, commodore Nicholson was requested to attend with the Society, as a member…”, and he appears also to have signed the New York Society’s membership book. In 1790 Nicholson was a resident of the East Ward of New York City with one other male over sixteen years of age, one female, and four other free persons. If one may judge by the arrangement of the returns, Nicholson lived only a few doors from “Anthony V. Demesser”, whom we suspect to have been Claude Antoine Villet de Marcellin [an Original Member of the Society], a fellow-member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania. Their post-war lives were very divergent.

In New York Nicholson’s exhibited political sentiments quite different than those of the majority of Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary officers, who were “conservatives”, “Republicans”, and, finally, “Federalists”. A myriad of causes, often fuelled by hostility to Alexander Hamilton and his policies, propelled the New York officers into the ranks of the “Anti-Federalists”. Nicholson was nevertheless in charge of the naval welcome to Washington as he arrived in New York harbor for his first inauguration in April 1789. On the other hand,

Apparently the Philadelphia Antifederalist group had first given serious considerations to the national election in September [1792]. It was then that [Alexander James] Dallas made a journey to New York City and spent much time in the circle of George Clinton, the Livingstons, Commodore James Nicholson and Aaron Burr. These practical politicians of the Empire State were opposed to Hamilton, not merely as the promoter of a national economic and political system, but as the head of a state party with which they had fought regularly since the Revolutionary period. They shared the views of the Pennsylvania Antifederalists on the practical and philosophical aspects of politics.

Another author has said, “His [Nicholson’s] house on William Street, one of the most valuable in the city, was the headquarters for the followers of Burr and Jefferson….He once had a tiff with Alexander Hamilton and the duel that threatened possessed a considerable charm for him, now an irascible and choleric old man.”

An example of Nicholson’s “irascibility” found its way into the New York Journal of 14 May 1794. In April the elections for the New York Assembly had resulted in a clean sweep for the Federalists ; Nicholson was President of the opposed Democratic Society of New York, and perhaps was feeling tender on the subject of politics:

Finding a report industriously circulated, that Commodore Nicholson of the democratic Society of this City, had declared to General [Samuel Blachley Webb] that he believed the President of the United States had received British gold, or words to that amount, he [the writer] sought to check that report and he found it entirely unfounded on fact.

Nicholson wrote in protest to Webb on 14 May, and on 18 May Webb replied,

…I do certify that you did not say that you believed the President of the United States was Bribed by British Gold – but at the same time…You railed with great Violence against the President and the Secretary of the Treasury, called the President an Aristocrat, which you declared was fully evinced by his Nomination to Offices of importance, [of] Men of Aristocratic Principles, and combated with warmth every argument which I used in their defence, from an Attack which appeared to me ill-founded and unjustifiable, – and in conclusion asked me “Do you know what has been attempted by British Gold in France” -my answer was I did – on which you said “You believed or you should not be surprized, if the same Game was played with the Officers of our Government,” or words to that effect, – this you said with much warmth….

In 1801 Nicholson was a delegate to the Convention of the State of New York; in the same year he was rewarded by the Jefferson administration by being made Commissioner of Loans. On 2 September 1804 James Nicholson died at his house in Greenwich Village, leaving one son James Witter Nicholson (1773-1851), who married Ann Griffin of Philadelphia, and five daughters. Of these, Hannah (1756-1859) married Albert Gallatin, the noted Anti-Federalist of Western Pennsylvania.