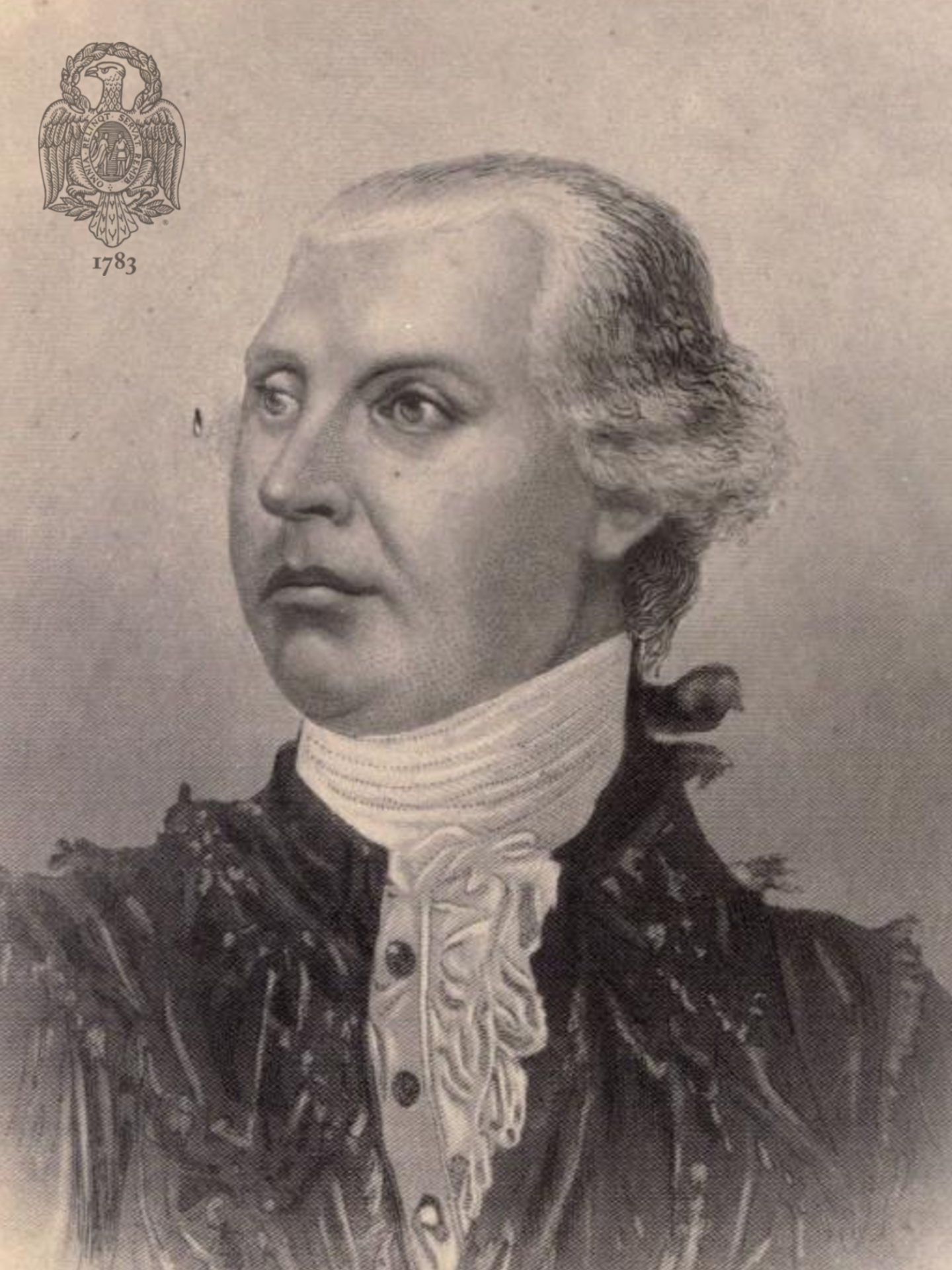

Capt. Thomas Butler

Thomas was the third son of Thomas and Eleanor (Parker) Butler, born 28 May 1748 in what was then considered Lancster County; two years later it became Cumberland County. He was destined for the law, and was a student of James Wilson, but on 5 January 1776 was commissioned First Lieutenant in the company commanded by his brother William in the Second Pennsylvania Battalion. He remained with the unit when on 12 March 1777 it was accepted into the Continental Army as the Third Pennsylvania Regiment, and indeed was still a company commander when the Pennsylvania Line was reorganized on 1 January 1781; Thomas thereupon retired.

The Second Battalion was among those in the unfortunate Canadian Campaign of 1776, and after retreating from Montreal, fell back to Fort Ticonderoga, where the enlistments of the men ran out on 5 January 1777. As has already been pointed out, most of the men remained on duty after that date, and the regiment finally returned to Pennsylvania in February, “in a Raged [sic] Dirty Condition, Enough to affright an Indian from Inlisting.”

Many of the officers and men re-entered the service in the Third Pennsylvania Regiment which joined the main army in the spring of 1777. At Brandywine, on 4 October, the regiment was in the right wing and was among the first to come under the British attack. Here, Thomas Butler courageously rallied the men who had begun to give way, and the enemy was again subject to severe fire from the American lines. For this he was thanked on the field by none other than Washington himself.

The regiment was next engaged at Germantown, on 4 October, where it was at the center of the American line in General Thomas Conway’s brigade which had almost succeeded in breaching the British lines when the American left wing gave way, causing the offensive to collapse. During the winter of 1777-1778 the Third was at Valley Forge where Butler took the Oath of Allegiance on 11 May 1778.

His regiment next was engaged at Monmouth., and it was here, on 28 June 1778, that Anthony Wayne’s efforts in rallying the Pennsylvanians saved the day and almost won it. Wayne’s efforts were in a sense extempore, for he used the troops that came to hand and probably not all the Third Regiment were committed. But Thomas Butler was thanked by Wayne for “defending a defile in the face of a severe fire from the enemy,” while the Ninth Regiment, commanded by his brother, Colonel Richard Butler, made their escape.

Thomas Butler remained a company commander in the Third throughout its history, at Middlebrook, Northern New Jersey, Morristown, and when it was marched to West Point by Wayne on 25 September 1780 to cover an expected British attack, provoked by Arnold’s treason. On 1 January 1781, at Morristown, the men of the Third Regiment joined in the general mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line. It was at that time that the regiment effectively ceased to exist, as has previously been explained.

On 1 August 1783 Thomas Butler “Junr[,] Captn Jany 3d 1776 deranged the 1st Jany 1781” signed the “Lancaster Roll of the Members of the Cincinnati Society,” together with his brothers Richard, William and Edward.

Thomas Butler then turned to farming in Cumberland County but like his brothers again returned to the military, as a Major of the Levies in 1791, when St. Clair mounted his offensive against the northwest Native Americans. At the battle of 4 November 1791, says John Linn Blair, “he headed a charge on horseback, though his leg had been broken by a ball. It was with great difficulty that his surviving brother Edward removed him from the field.”

Butler remained in the military, and on 11 April 1792 was commissioned Major of Infantry, U. S. Army. In 1794 Butler became commandant of Fort Lafayette at Pittsburgh, and on 1 July 1794 was commissioned Lt. Colonel. He thus was in a particularly sensitive, not to say vulnerable, location when the Whiskey Rebellion broke out. On 16 July 1794 the rebels attacked the house of John Neville [an Original Member of the Society], Collector of Excise in western Pennsylvania, and the first shots were fired. There was danger from the first that the rebels would turn toward the military base for armament, but it was said that Butler prevented this happening at Pittsburgh largely through the prestige of his name, hallowed in the West, and by threats of what he could do, rather than by actual force of arms.

On 1 November 1796 Butler was assigned to the Fourth United States Infantry and the next year was sent to Tennessee to remove unauthorized settlers from Native American lands, in a manner similar to that used immediately after the Revolution in Ohio. Butler’s operations, however, were conducted in such a manner that by 1801 he was one of the most popular men in Tennessee, even though, like most of his fellow Revolutionary War veterans, he was a Federalist. On 1 April 1802 he was made Colonel of the Second Infantry.

Since 1796, at the death of General Anthony Wayne, Brigadier General James Wilkinson of Maryland had been the senior commander of the Army. It was he with whom Colonel Butler was about to do battle over what now seems a minor matter: not so for the men involved. In July 1801 Wilkinson as commanding general issued a general order prohibiting the wearing of long hair, specifically queues, in the army. This struck forceably against the habit and custom of the military, particularly those men whose careers started with the Continental Army. But there was also a subtle significance as well: short hair was then looked on as a symbol of republican triumph, epitomized by the French Revolution. Not all Americans were in sympathy with that movement which had ruined the Bourbons, America’s old allies. And the ultra-Republican Francophile Thomas Jefferson had just become President.

While Wilkinson was senior, Butler was second in command, and when the former visited Tennessee in 1801 Butler asked for an exemption from cutting his hair. Butler said he granted the request in deference to Butler’s infirm health, but in 1803 the permission was withdrawn as Wilkinson then said Butler’s health was improved, and this single exemption was bad for the army’s morale. At the same time Butler had tarried in going to a new post at Fort Adams on the Mississippi. Butler refused to be terrorized, and in May was ordered to court-martial.

The court sat at Frederick, Maryland, from 21 November to 6 December 1803. Butler argued invasion of personal right in the matter of his hair, and that the delay in going to Fort Adams had been unavoidable. He was found guilty of not having his queue cut off, but innocent of disobeying the order to move.

Butler did in fact move to New Orleans late in 1804 and almost immediately was arrested by Wilkinson because of his conviction in the matter of his hair, which he retained. That, his commanding officer said, constituted mutinous conduct. Wilkinson found means of selecting a court that was favorable to his views, and it convened in July 1805, Wilkinson remaining aloof in St. Louis. Besides the heat, New Orleans was fighting a plague of yellow fever.

The court martial found Colonel Butler guilty of disobedience of orders, and mutinous conduct, and sentenced him to be suspended from command and to lose all pay and emoluments for one year. Wilkinson, of course, had to review and confirm the findings of the court, which he did on 20 September 1805. But in a sense Colonel Thomas Butler had the final say: he had died in New Orleans on 7 September, no doubt from the rigors of the trials, but certainly from yellow fever. He is said to have left instructions: “Bore a hole through the bottom of my coffin right under my head, and let my queue hang through it, that the dammed old rascal may see that, even when dead, I refuse to obey his orders.”

Thomas Butler had married Sarah Semple of Pittsburgh, and there were three sons and one daughter of the marriage.