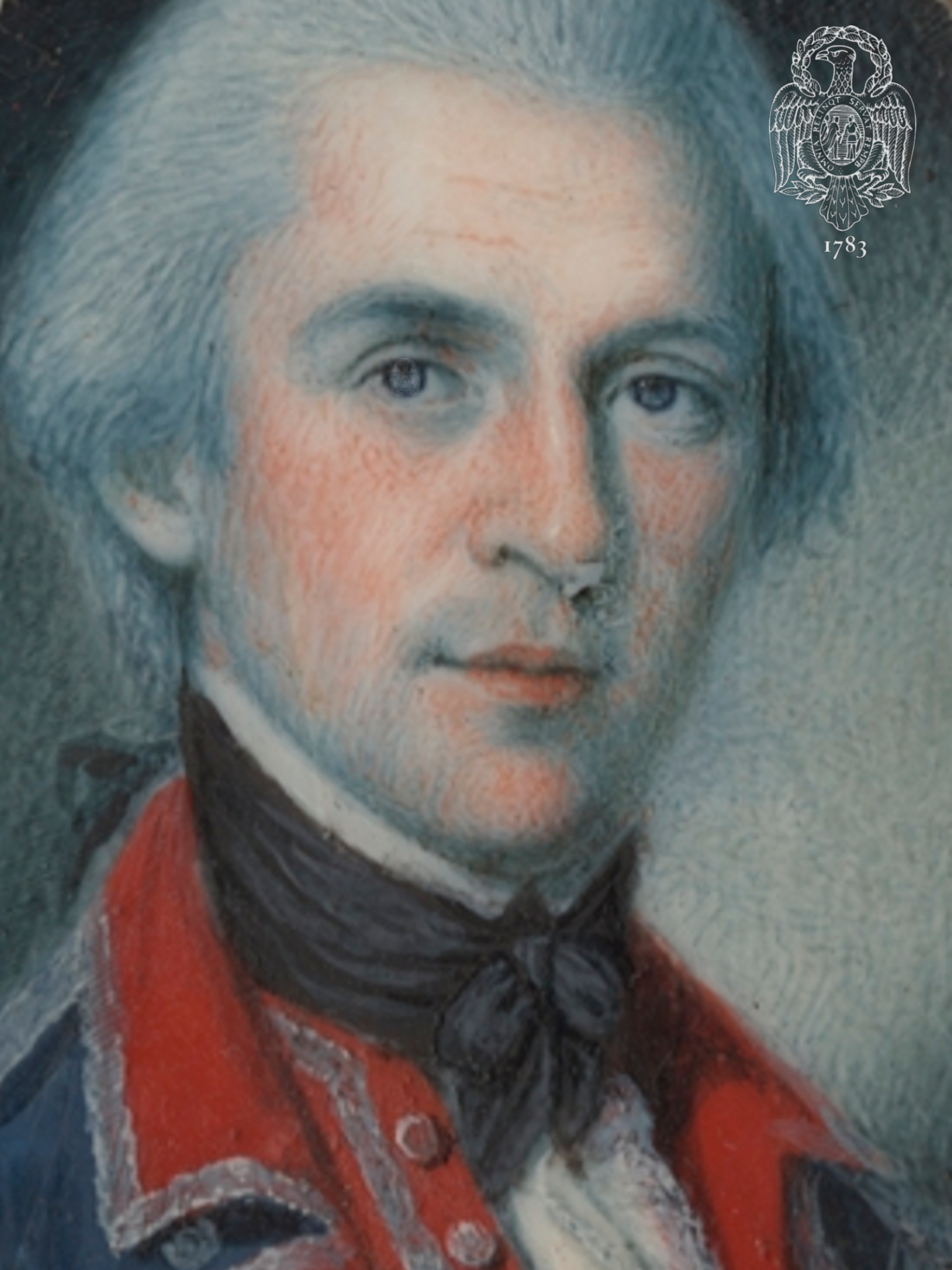

Col. Walter Stewart

Walter, the son of William and Ann (Hall) Stewart, was born in 1756 in Londonderry, Ireland. He was in Pennsylvania prior to the Revolution but the exact year is not specified. His literate correspondence and elegant handwriting indicate a well-grounded Eighteenth-Century education. George Washington Parke Custis (1781-1857) described Stewart as having a “fair, florid complexion, was vivacious, intelligent, and well-educated, and it was said was the handsomest man in the American army.”

At the age of twenty Stewart was commissioned Captain in the Third Pennsylvania Battalion, Colonel John Shee, on 6 January 1776. He commanded the sixth company, but as early as 26 May Stewart was made aide-de-camp to General Horatio Gates with the rank of Major. By an Act of Congress of 19 November 1776 it was “Resolved, that Major Stewart who brought the late intelligence from General Gates, and who is recommended as a deserving officer, have the rank of Lieutenant Colonel by brevet, and be presented with a sword of the value of one hundred dollars.” It is evident that Stewart had made the most favorable impression on Gates, and this was to have future results.

In October 1776 Pennsylvania organized the Pennsylvania State Regiment from the remnants of Samuel Miles’ Pennsylvania State Rifle Regiment and Samuel John Atlee’s Pennsylvania State Battalion of Musketry, both of which had been decimated at Long Island in August, with both colonels captured. The proposed colonel of the amalgamated regiment was John Bull of Montgomery County. As Bull had served in neither of the two regiments, the officers objected so strongly to his appointment that Stewart was named in his stead, and Bull was made Adjutant General of the Pennsylvania Militia. Lieutenant James McMichael [an Original Member of the Society] wrote of this episode in his diary,

June 17, – At 10 A.M. we appointed for a meeting of the officers in Elbow Lane [Philadelphia], where we set to write out our resignations. I was one of the writers and wrote my own resignation with sixteen more, and we then marched to the State House to deliver them. On the way we were stopped by Col. [Lewis] Farmer, who gave us the pleasing news that Col. Bull was not to command us and that Col. Stewart was appointed. Col. Farmer further informed us, that Col. Stewart requested all the officers of the regiment to meet him at 4 P.M. at the City Tavern. We immediately repaired to our Quarters where we dressed ourselves and at the time appointed we waited on Colonel Stewart, to our great satisfaction, when after drinking some gallons of Madeira, we returned to our Lodgings much satisfied.

The Pennsylvania State Regiment was organized as a “state troop”, and was not incorporated into the Continental Army until 10 June. Within a month it was being referred to as the “Thirteenth Pennsylvania Regiment”, but it did not officially acquire that designation until November. It had but a brief existence: it was decided that the regiment be incorporated into the Second Pennsylvania Regiment, Colonel Henry Bicker [an Original Member of the Society] on 1 July 1778. Inasmuch as Stewart was the senior colonel he then acquired command of the Second Regiment and Bicker left the army as supernumerary.

The principal operations of the State Regiment were at Brandywine on 11 September and at Germantown on 4 October 1777. The combined actions cost the regiment twenty-two wounded and sixteen either killed or missing. The Thirteenth Regiment was at the minor action at Whitemarsh in November and then marched to Valley Forge for the winter encampment of 1777-1778. There Stewart and his officers took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States on 12 May 1778. John Trussell speaks of Stewart at Valley Forge:

Although the number of his troops was dwindling, Colonel Stewart took positive action to improve the effectiveness of his officers. To develop esprit and mutual good feeling, he instituted a program whereby officers of various grades took turns in hosting a succession of dinners for each other. To develop or enhance their military competence, he carried out a series of what in more modern terminology would be called “tactical walks,” in which he took his officers around the camp, discussing the best uses of the terrain against the various avenues of approach which an attacking enemy might use.

In the new year the Thirteenth was present at Monmouth on 28 June 1778, and Stewart was wounded in that action. That battle effectively marked the end of the regiment, not because of enemy action: it was absorbed by the Second Pennsylvania Regiment on 1 July 1778 and Stewart became its Colonel.

Monmouth was the last major operation in the North. The regiment patrolled northern New Jersey until entering winter quarters at Middlebrook, 1778-1779. In October 1779 it was in garrison at West Point under Wayne’s command, and again wintered at Morristown, 1779-1780. In April 1780 Stewart was one of a number of army officers, including Wayne and Henry Lee of Virginia, who assembled at the New Tavern in Philadelphia and published their intention of ostracizing “any person or persons, who have exhibited by their conduct an enemical disposition or even luke warmness, to the independence of America,…we will hold any Gentleman bearing a Military commission, who may attempt to contravene the object of this declaration,…as a proper object of contempt,…”.

In the Spring the regiment was engaged at Paramus on 18 May and at the Blockhouse at Bergen Heights, New Jersey on 7 June, where two lieutenants were killed in that futile assault. In September the Second marched with Wayne to welcome Rochambeau at Hartford, and almost immediately afterwards rushed with Wayne to West Point to counter Arnold’s treason. In December the regiment moved to Morristown for winter quarters and there the men, threatened by their comrades, reluctantly joined the general revolt of the Line. Although the reform of January 1781 preserved a Second Regiment, it was a paper organization.

A good account of day-to-day occurrences in the regiment after the mutiny can been found in the diary of Captain Joseph McClellan: the time was spent recruiting and tidying up the consequences. Then, in Philadelphia on 11 April McClellan wrote, “…Col. Stewart was married to Miss McClanachan [sic] this day.” The bride was Deborah, born 4 June 1763, the daughter of Blair and Ann (Darrah) McClenachan, and the marriage was performed by the Rev. Mr. William White, at St. Paul’s Church, Philadelphia. McClellan continued his narrative on 5 May, saying, “A detachment of 3 companies of the 2nd Regiment marched from Downingtown for York… May 11. Set out from Lancaster, with Captain [Jacob] Stake [an Original Member of the Society], and got to York at 5, P.M….May 26. Marched from York at 9, A.M.” This was the beginning of the long march to Yorktown, thence to Charleston. Lieutenant Jacob Weidman [an Original Member of the Society] contributes an incident of the march:

[August] 27th. This day, 2 o’clock, P.M., a number of us crossed the James River in a canoe, in order to take a view of an elegant building and garden belonging to Colonel Mead….In the evening Lieut. [Joseph] Collier and self went to Capt. [Robert] Wilkins’ [sic, q.v.] tent, and there spent the evening and part of the night…. August 29th….This day Captains Wilkins and [John] Irwin [an Original Member of the Society] of the Second Battalion were arrested by Col. Walter Stewart in consequence of our last night’s proceedings.

Captain Irwin by this time was serving in the Commissary Department, and no doubt had access to some supplies of good cheer. Lieutenant John Bell Tilden [an Original Member of the Society] had at the same time been drinking tea with the Byrd family at “Westover”. He recorded taking his leave of them at “…10 o’clock, and on my arrival at my tent, am surprised to find the officers of the next tent sitting up, walk to their door, when I am detained to drink grog. An odd adventure happens about midnight…. The “odd adventure” was Colonel Stewart’s having the party-goers arrested for unseemly behavior, but Wilkins, at least, was acquitted.

Stewart returned to Pennsylvania very soon after Cornwallis’ surrender. When Wayne applied to Washington on 4 November for a similar leave, Washington stiffly replied, “Your application is not a little distressing to me;…Colo. Stewart is already gone and Col. [Richard] Butler on account of his health is going….” Wayne just as stiffly replied that he would stay in the South, and did so. Stewart wrote him from Philadelphia the letter of 28 December, already quoted in the first part of this study, decrying the political situation in the Commonwealth. The day before this, 27 December, Stewart’s eldest son William had been born, and Dr. White christened the child, whose godfather was General George Washington.

Colonel Stewart did not return to the South and it is very possible that, like many of his men, he had contracted malaria there. In October 1782 he wrote Washington from Philadelphia that he was suffering from a “fever” that kept him from any duty for the rest of the year. On the re-formation of the Pennsylvania Line on 1 January 1783 he retired from the Line. He did not however retire from the Continental Army, as at Washington’s request he became Inspector General of the Northern Army, thus again coming under the command of Baron von Steuben in whose Division the First Pennsylvania Battalion had been at Yorktown.

Stewart by 1783 was strongly attached to the emerging “party” favoring a strong central government for the new United States, often called “nationalists”, whose tenets were embodied in the sentiments and writings of Alexander Hamilton and Robert Morris, The Financier. Stewart’s politics were also tempered to an extent by his being a “holder of a large amount of public securities.”

A result was Stewart’s involvement, to whatever degree, in the “Newburgh Conspiracy”. Washington was well aware of the discontents of the Army, but he apparently felt that things at Newburgh were under control until Stewart’s arrival there on 8 March 1783 bearing messages from the “nationalists” to their military partisans. On 12 March Washington wrote to Hamilton in Congress that all was tranquil in camp until after the arrival from Philadelphia of “a certain gentleman”. The events of the “Conspiracy” are not to be rehearsed here; Washington brought the officers to their senses in his famous speech of 15 March and the Continental Army moved tranquilly, if unhappily, to its demise by the end of the year.

With other officers at Washington’s headquarters Stewart had the distinction of signing the great “Parchment Roll” of the General Society of the Cincinnati at its founding in May 1783. He signed also the Pennsylvania “Parchment Roll” and the “Pay Order of 1784”, and he served on the Standing Committee of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania from 1789 to 1794.

After the war Stewart pursued the profitable role of a Philadelphia city merchant. The record of the births of his children shows that in 1786 the Stewarts were in Ireland, and in July 1787 they were in London. Stewart’s character as a “Republican [Federalist] stalwart” is reflected by his 1788 correspondence in 1788 with William Irvine [an Original Member of the Society] and others hoping for a revision of Pennsylvania’s “radical” Constitution of 1776. The census of 1790 lists Stewart on the north side of Market Street in the Middle district of Philadelphia. Although there were many businesses this was a choice area: his neighbors were William Shippen and Nathan Sellers, and not far away lived Daniel Brodhead [an Original Member of the Society]. Stewart was active in various organizations: the Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, the Hibernian Society, of which he was Vice President, the Hibernian Fire Company. He was a manager of Canal Lottery Number 21 and a member of the Dancing Assembly of the town. From 1793 until 1796 he was Inspector of Revenue and Surveyor of the Customs at the Port of Philadelphia, and in 1794 was one of the commissioners appointed for the cultivation of the vine in the state. In 1794, like many of his fellow-officers, Stewart was again called to military service as Major General of the First Division of the Pennsylvania Militia.

Walter Stewart died in Philadelphia on 14 June 1796, aged forty years. He was given a military funeral at St. Paul’s Church, Philadelphia, where the family of Blair McClenachan had a family vault. William White, by that time Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania, who had married Stewart and baptised his children, officiated. Mrs. Stewart survived until 22 March 1823. There were eight children of this marriage. Singularly enough, of the five sons every one died in a foreign country but the eldest, William, who was lost at sea in 1808.