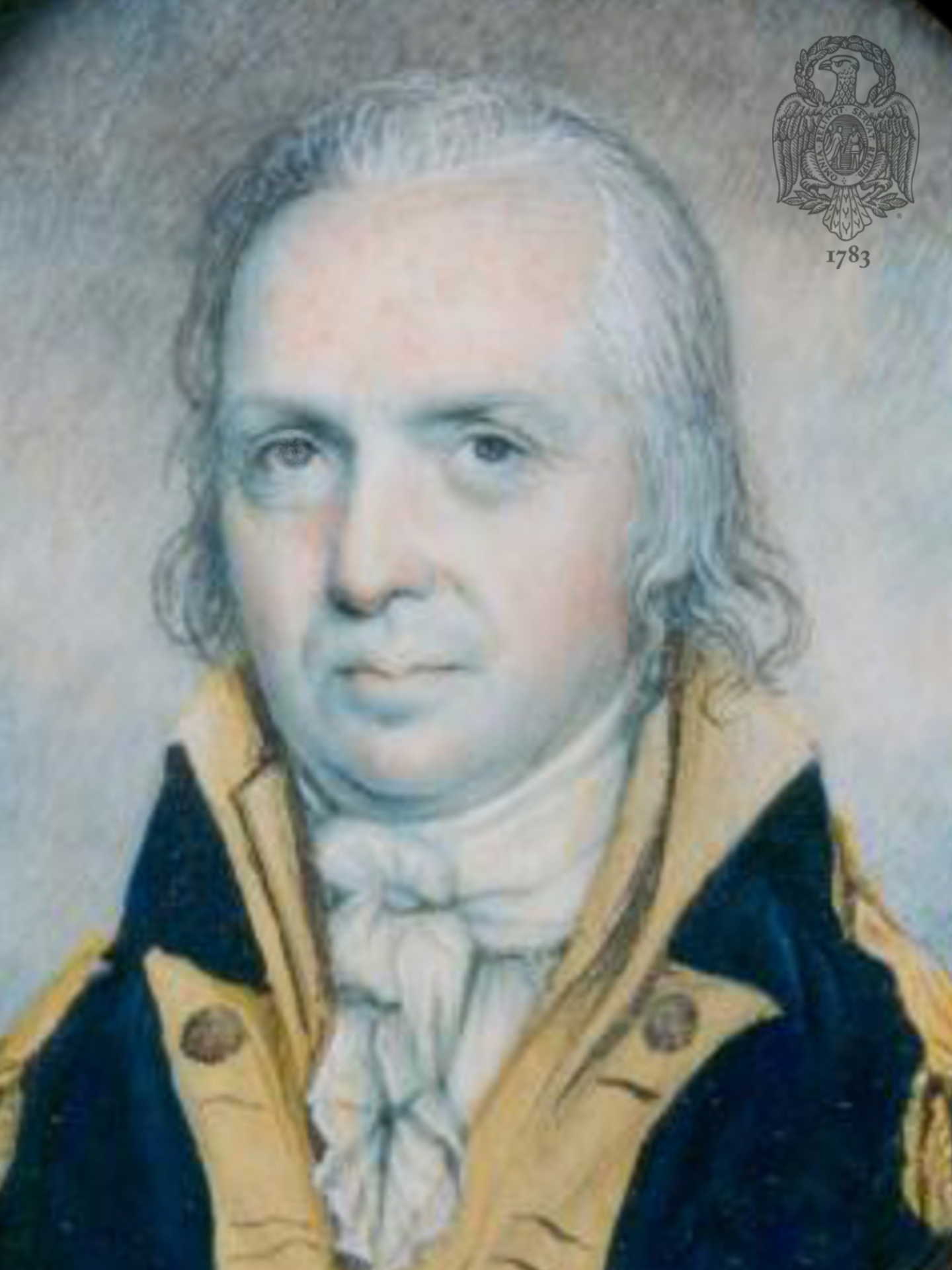

Lt. Col. Josiah Harmar

Harmar was born in Philadelphia 10 November 1753. His background lay, like that of a good many other officers from eastern Pennsylvania, in the Society of Friends, but his actual parentage is obscure. He was educated in the Friends Public School in Philadelphia, conducted by Robert Proud, the historian. Very little more is known of Harmar’s young years.

On 27 October 1775 he was commissioned captain in the First Pennsylvania Battalion. Under Colonel John Philip de Haas the battalion marched to Canada, where Harmar first saw action in reinforcing Benedict Arnold, pinned down at La Chine, on 27 May 1776. With the other American troops the First Battalion retreated to Ticonderoga, and was sent back home 13 November. The battalion was then reorganized as the Second Pennsylvania Regiment with many of its original men. On 1 October 1776 Harmar was promoted Major of the Third Regiment, but on 6 June 1777 he received a further promotion as Lt. Colonel of the Sixth, whose colonel, Robert Magaw, was a prisoner of war. Harmar therefore in fact commanded the regiment, and he remained in command until made Lt. Colonel Commandant of the Seventh Regiment on 8 August 1780. With the re-formation of the Pennsylvania Line in 1781 he was transferred to the Third Regiment, Colonel Thomas Craig.

It is evident that Harmar was considered the possessor of considerable military skills which Washington and the Congress were very willing to put to best use. His frequent transfers represent attempts to strengthen weakened regiments, or to provide new regiments with talented officer material: witness Washington’s writing at a later date that Harmar was one of a group of officers, “…personally known to me as some of the best officers who were in the Army”.

Harmar marched south with Wayne and was present throughout the campaign in Virginia. It was Harmar’s and Major Evan Edwards’ [an Original Member of the Society] timely reinforcement of Wayne at Green Spring, Virginia, on 6 July 1781 that decided the latter’s sensational charge of the British line, impeding it sufficiently to give Lafayette time to intervene and save the Pennsylvania Line from Cornwallis’ army. In August in a skirmish near Richmond Harmar had his horse shot from under him, and he stated that he there barely escaped with his life. At the Siege of Yorktown Harmar was Lt. Colonel of Richard Butler’s Second [Provisional] Battalion of Anthony Wayne’s Brigade.

Wayne re-formed the Pennsylvania troops into two provisional regiments on 2 November 1782, and Harmar then became Lt. Colonel of the first commanded, by Colonel Daniel Brodhead. When the Pennsylvania Line marched to Charleston to join Nathanael Greene’s army Harmar was with them, and he served as Adjutant General to Greene in 1782. The final reformation of the Pennsylvania Line occurred on 1 January 1783, with Brodhead and Harmar in command of the First Regiment. In June the Pennsylvania troops were sent home and Harmar was mustered out with them on 3 November 1783.

The Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania when then in process of being formed and Harmar signed the “Barracks Roll” of the First Pennsylvania Regiment in August 1780.3 Later he signed the Parchment Roll of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania and the “Pay Order of 1784”. Harmar was elected first Secretary of the Pennsylvania Society and remained in office until succeeded by William Jackson in 1785; re-elected Secretary in 1793, he declined the office.

Soon after returning to Pennsylvania, Harmar was selected as his private secretary by Thomas Mifflin, elected President of the Continental Congress in November 1783. The Congress’ first, imperative, business was the ratification of the treaty of peace with Great Britain, but Congress was then in recess, was not due to reconvene in Annapolis until later in the month, and even by January 1784 a quorum had not assembled. The Paris commissioners had agreed that the respective ratifications be exchanged within six months, and sooner if possible. As the treaty had been signed on 3 September, four months had already passed by the beginning of the new year. Desperate that this important work be done, Mifflin sent Harmar to collect missing delegates from New Jersey, Connecticut and South Carolina, and the ratification was accomplished on 14 January 1784.

It was therefore natural when Congress hurredly resolved that the ratification be sent to France “under the care of a faithful person”, that Harmar be chosen. Because of the season the weather was inclement, but Harmar finally found passage on L’Amerique out of New York on 21 February. Another month had thus been lost; as the rough passage took thirty-three days, Harmar did not make land at L’Orient until 25 March, three weeks after the deadline for the exchange, and did not reach Paris until 29 March. There, to his undoubted relief, he found that the wise Benjamin Franklin, anticipating a delay, had made arrangements with the British to adjust the schedule. Harmar, with heart-felt relief, reported to Mifflin, “I therefore have the satisfaction to inform your Excellency All is well.”

Harmar then was able to enjoy Europe for some three months, during which time he visited England, met Lafayette, for whom he had letters, and was presented by him to Louis XVI and the Queen. Harmar was fortunate in this connection, for the insufficient funds Congress provided for him had to be supplemented by a loan from the Marquis. They returned to America together, arriving at New York on 4 August 1784.

Even in his absence Harmar’s career was being shaped for him. On 3 June 1784 the Congress created the United States Army; through Mifflin’s recommendation on 12 August Harmar was given the command as Lieutenant Colonel of the United State Infantry Regiment and Commander of the Army. Harmar must unquestionably have been elated, but he also had cause for personal celebration as on 10 October he was married at Old Swede’s Church, Philadelphia, to Sarah, daughter of Charles and Mary (Gray) Jenkins, Quakers of that city. Their honeymoon was to be Harmar’s new command at Fort Pitt, and thence they departed about a week after the marriage.

Harmar’s immediate mission, after consolidating Fort McIntosh below Pittsburgh as headquarters for his “army” of some two hundred one-year men, was to provide the necessary military support for the forthcoming treaty with the Northwest Native Americans, consummated in January 1785. But this was only the beginning of his larger responsibility for “securing” the territory north of the Ohio against the tribes, their allies the British (still controlling the frontier forts) and, not least, American squatters. This story is a long and a complicated one, extensively treated by historians of the period and of the area. Always short of men, money and supplies, Harmar performed as well and nobly as can have been expected from the truly exceptional American men of the generation. He was breveted Brigadier General 31 July 1787, and was nominated, but not elected, a delegate to the First Congress of the United States, 1789

In 1790 the defining moment of Harmar’s career came. He had successfully established a chain of some five forts along the north shore of the Ohio River and up the Wabash. Arthur St. Clair, former commander of the Pennsylvania Line, was Governor of the territory. But the British still held the frontier forts, and, in spite of the strengthened American presence, settlers in the area were increasingly subjected to Native American raids and harassment. As the tribes were supplied from the British at Detroit and were strongly influenced by the counsels of the British Indian department in Canada through its western representative, the Pennsylvania renegade Alexander McKee, confrontation with the Native Americans ran the risk of a new war with Britain.

A preemptive stroke against the strong Native American concentration on the Miami River was prepared and authorized by Washington and Knox, Secretary of War. Harmar’s small army was to be supplemented by 1500 militiamen from Pennsylvania and Kentucky to assemble at Forts Washington (Cincinnati, Ohio) and Steuben, and the operation began on 26 September. Harmar succeeded in burning Native American towns and destroying crops, but the campaign failed because of lack of supplies and armament, and because of the usual lack of discipline in the militia. Harmar returned to Fort Washington on 3 November to report a loss of 183 men. The most rivetting fact was that 79 were regulars; the most telling, that the Americans did not bury nor retrieve their dead.

Both Harmar and St. Clair reported the campaign a success. But Washington and Knox, their opinions influenced by public sentiment, thought differently and Knox wrote Harmar in January 1791,

The general impression upon the result of the late expedition is that it has been unsuccessful, that it will not induce the Indians to peace, but on the contrary encourage them to a continuance of hostilities, and that, therefore, another and more efficient expedition must be undertaken. It would be deficiency of candor on my part were I to say your conduct is approved by the President of the United States, or the public. The motives which induced you to make the detachments…require to be explained….I further suggest to your consideration…to request the President of the United States to direct a court of inquiry, to investigate your conduct in the late expedition.

It was obvious that Harmar had lost the confidence of his powerful superiors, a conclusion emphasized in March when Knox notified him that Arthur St. Clair had been appointed Commander of the Army. Exactly one year later St. Clair suffered an even worse defeat at the hands of the northwest tribes.

The court of inquiry which convened at Fort Washington in September, General Richard Butler [an Original Member of the Society] presiding, exonerated Harmar and placed the blame for failure on the undisciplined and unequipped militia which made up the bulk of his command. Harmar retained the confidence of his own officers but he had already decided to resign his command. Ebenezer Denny’s observations in September 1791 were typical of his officers’ sentiments:

…The court made a report to the commander-in-chief, highly honorable to General Harmar. It was impossible for me not to be affected by the determination of General Harmar. I knew that he only waited for the march of the army [under St. Clair, in the new campaign], when he would ascend the [Ohio] river with his family and retire to civil life. My secret wish was to accompany him; he discovered it, and informed me that he would apply for an officer’s command to escort and work his boat to Pittsburgh, and had no doubt but that General St. Clair, upon being asked, would order me on that service. I made the request in writing. Was answered that it could not be granted. I stayed with General Harmar and his family until the last moment. He conversed frequently and freely with a few of his friends on the probable result of the [new] campaign – predicting a defeat. He suspected a disposition in me to resign; discouraged the idea. “You must,” said he, “go on the campaign; some will escape, and you may be among the number.”

Harmar resigned from the army on 1 January 1792. He was thirty-nine years old, and the Army was thereafter permanently deprived of his experience and organizational ability.

When Harmar returned to civil life in Pennsylvania his old patron Thomas Mifflin, now the Governor of the Commonwealth, stepped forward once again and Harmar was made Adjutant General of the Militia of Pennsylvania on 11 April 1793. He thus exercised during the Whiskey Rebellion the position he had held under Nathanael Greene during the last months of the Revolution, and it is possible that it was in just such a capacity that his talents were most fully realized. But there is a certain irony, nevertheless, in the situation: a hardened veteran of the “Regulars” in both the Revolution and the early Indian wars, who it is not too strong to say despised the militia, was then in the controlling position over it. (It was Harmar who, in September 1794, gave the orders for each Pennsylvania county’s militia assembly ). Many frontiersmen blamed Harmar’s expedition for stirring up in-creased Native American depredations and this did not increase his popularity in Western Pennsylvania. He remained Adjutant General until 26 February 1799.

After his public services General Harmar purchased the well-known inn, “The Conestoga Wagon” from his brother-in-law Samuel Nicholson [an Original Member of the Society] on 19 September 1798. He lived at home, near Philadelphia, in a large house which he called “The Retreat” near Gray’s Ferry on the Schuylkill River. Ebenezer Denny’s son, Harmar Denny, visited his eponym in the latter’s old age, and described him as “…tall and well built, with a manly port, blue eyes, and a keen martial glance. He was very bald, wore a cocked hat, and his powdered hair in a cue [sic]”.

Josiah Harmar died 20 August 1813 and his funeral was from the house of his sister-in-law, Mrs. Samuel Nicholas in 12th Street, Philadelphia. He was buried in St. James’ Churchyard, Kingsessing, and was survived by his wife and five children; a daughter had died in infancy. Of these children three were sons. The oldest, Charles Jenkins Harmar, went out from Philadelphia as supercargo on the ship Rover; he died 14 June 1806 at Cap François [Cap Haitien], Haiti.

In 1838 Sarah Harmar, giving her age as seventy-eight, applied for a pension as widow of the Colonel, and stated she could not appear in court because of bodily infirmity. The pension was allowed at the rate of six hundred dollars per annum. Mrs. Harmar was still living, aged 82 in 1842, in Passayunk (South Philadelphia).