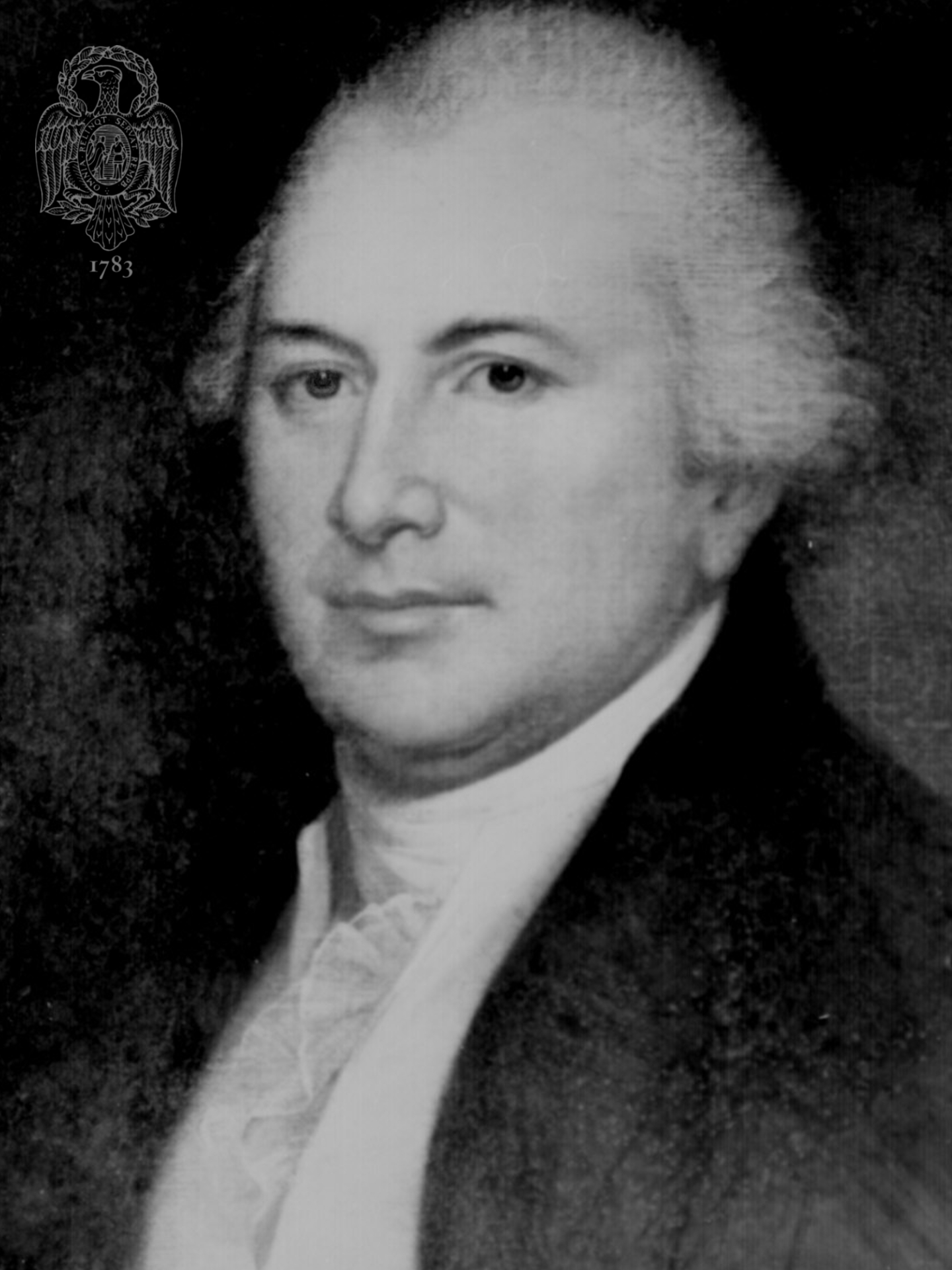

Maj. Gen. Thomas Mifflin

Mifflin’s name is familiar to all or most Pennsylvanians: there is Mifflin Street in Philadelphia and doubtless elsewhere; there are Mifflintown, Mifflinburg and Mifflin County; Columbia, Dauphin and Lycoming Counties all have Mifflin Townships. But the first Governor of Pennsylvania after independence has never been the subject of a definitive and impartial biography. This is partly due to a lack of personal letters, diaries and similar materials, which has resulted in Mifflin’s biography being identified with that of the history of the State during the period of his dominance.

Thomas, the eldest son of John and Elizabeth (Bagnell) Mifflin, was born in Philadelphia on 10 January 1744. His father was a successful and prosperous merchant, a member of the Provincial Council and prominent in the affairs of the city and colony. Like a number of other officers of the Pennsylvania Line, Thomas Mifflin came of a Quaker background; he was disowned by the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting on 28 July 1775 because of his military involvement. He received his early education at a Quaker school, and graduated from the College of Philadelphia, where his father was a trustee, in 1760. He was destined for a mercantile career and entered the counting house of William Coleman of Philadelphia, but in 1764 sailed for Europe where he visited England and France. Back home by 1765, he established a successful business with his younger brother George at Front and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia.

In February 1768 Mifflin became a member of the American Philosophical Society, serving as a secretary for some time. His fellow members included Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson and Charles Thomson, men already prominent and to become even more so within a few years. Mifflin’s place in provincial society, coupled with natural gifts in oratory, presaged an eminent position, foreshadowed by his first public office as a Warden of the city, to which he was appointed in March 1771. The next year he was elected to the first of four successive terms in the Provincial Assembly; his prominent position as a radical therein was predictable from activities in opposition to the Stamp Act and in promoting non-importation. His natural inclinations were only strengthened by a visit to Boston in 1773, when he met John and Samuel Adams and other fiery Whigs. From 1774 to 1776 Mifflin was among the youngest members of the First Continental Congress. Although elected to the Second Congress, Mifflin’s attention then turned to the military.

The news of Lexington and Concord reached Philadelphia on 25 April 1775; on 15 June George Washington was selected as Commander-in-Chief; on or about the same time Mifflin was commissioned Major; on 23 June he was selected as Aide-de-Camp to Washington; on 14 August he was made Quartermaster General of the Army; on 16 August he was elected a member of the Philadelphia Committee of Safety; in October he was again elected to the Continental Congress; and on 22 December he was commissioned Colonel. In this dizzying manner Mifflin’s career unfolded. He was not a stranger to battle conditions: at Lechmere’s Point near Boston on 9 November 1775 his personal courage was remarked when a British raiding party was turned back by the Pennsylvania riflemen.

Much of Mifflin’s public career was distinguished by a gradual alienation from Washington. Whether this stemmed from their initial association is uncertain, but Mifflin did not long remain Washington’s Aide, and when on 14 August he was named Quartermaster General, Washington, rather enigmatically, wrote Richard Henry Lee that the appointment was made because he trusted Mifflin’s integrity, “–and finally, because he stands unconnected with either of these Governments; or with this, that, or t’other man; for between you and I [sic] there is more in this than you can easily imagine.” Mifflin undertook his new assignment eagerly and with industry, and he was appointed Brigadier General on 16 May 1776. Horatio Gates was commissioned Major General at the same time, and fate and history henceforth linked their names: they were life-long friends. Already, however, Mifflin’s enthusiasm for supplying the army was flagging: he desired battlefield duty. At his own request he was relieved of his Quartermaster’s duties in June 1776 and was succeeded by Stephen Moylan [an Original Member of the Society]. Mifflin was given command of a brigade composed of the Third and the Fifth Pennsylvania Battalions, Colonels John Shee and Robert Magaw [an Original Member of the Society], respectively. At the Battle of Long Island on 27 August it was Mifflin’s Brigade which covered the retreat of the American Army to Manhattan, hence the heavy casualties suffered by these battalions. Unfortunately, because of a mistaken or a misunderstood order, General Mifflin was rebuked by Washington for withdrawing his screening troops too soon. Military misfortune probably was avoided, but relations between the two men were not improved thereby. By 15 September the British held New York City, from which they were never dislodged until after the war’s end.

Moylan’s tenure as Quartermaster General was not a success and in September Mifflin was persuaded to resume that duty while retaining his brigadier’s rank. The change was well received by Congress and by Washington himself, and Mifflin was at Headquarters when fell the heaviest military blow thus far suffered by the Americans: the capture of Fort Washington on 16 November. Some 2800 Americans were taken, with large stores of ammunition and supplies, Mifflin’s responsibilities. Mifflin blamed Washington for the disaster, and in his view the defense of Philadelphia now became the critical element for the survival of Continental hopes. Mifflin was present at Trenton at Christmas, 1776, and Princeton on 3 January 1777, and he was promoted to Major General on 19 February. But when Washington’s defensive campaign failed to prevent Philadelphia’s capture, any surviving friendship between Mifflin and Washington vanished, and only the passage of much time bridged that gap.

Whatever the cause, Mifflin at York became identified with the mysterious “Conway Cabal”, and has sometimes been identified as the instigator. The debate about the Cabal has been alive for two hundred years and will no doubt continue to furnish fuel for historical speculation for many years to come. To what extent his involvement bore upon Mifflin’s discharge of duty as Quartermaster General is also questionable, but he soon began to feel the weight of criticism charging him with incompetence in office. Pleading ill health, Mifflin left the temporary capital at York for his country home at Reading, and on 8 October 1777 sent in his resignation both as Major General and as Quartermaster General. At the urging of Congress he continued in Supply until March 1778, but the was only more acrimony because of the suffering of the Army at Valley Forge. Unquestionably, the affairs of his department were in utter confusion when Mifflin was finally succeeded by Nathanael Greene in March, but much discord was due to Congressional interference and other factors beyond Mifflin’s control.

Mifflin was permitted to retain his rank as Major General without salary, and was made a member of the newly constituted Board of War, of which Horatio Gates was President. Both in the Board of War and in Congress questions were raised about Washington’s abilities: he had lost Philadelphia, Gates had gained Saratoga. Washington discovered the discontent not later than November 1777 and he soon sent for Congress’ review his letters and documents bearing on the situation. By January 1778 whatever plot that existed had failed: Gates, Mifflin and Conway were sent from York back to the Army. Mifflin rejoined on it 18 April, but concerned himself chiefly with defending his record as Quartermaster General. Although Mifflin demanded a court-martial to clear the air it was never convened; instead Congress granted him a million dollars to settle all claims against his office. Mifflin again submitted his resignation as Major General on 17 August 1778 and it was irrevocably accepted on 25 February 1779.

Mifflin turned to Pennsylvania politics and served in the General Assembly in 1778 and 1779. His posture there was conservative, and he advocated revision of the State Constitution of 1776 and the preservation of the charter of the College of Pennsylvania. When the charter was revoked and the University of Pennsylvania constituted in the College’s place, Mifflin served as a trustee from 1778 to 1791. In 1782 he was again elected to Congress and served until 1784; in 1783 he became President of Congress. It was thus his fate to accept Washington’s resignation as Commander-in-Chief in Annapolis on 23 December 1783.

General Mifflin signed the “Parchment Roll” of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania in 1783. He succeeded General St. Clair as President of in 1789 and held the office until 1799. In 1787 he was elected Vice President General of the General Society of the Cincinnati, where, at his death in 1799, he was succeeded by Alexander Hamilton.

In 1787 Mifflin was a delegate to the Federal Constitutional Convention and later assisted in Pennsylvania’s ratification assembly. In 1788 he was elected to the Supreme Executive Council of which he was President, and therefore President of the Commonwealth until 1790. He presided at the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention of 1789-1790, when the radical Constitution of 1776 was finally superseded. Now, however, there was evident a change in Mifflin’s political stance, and he offended his natural allies, the “Republicans” who were the victors when the new state constitution came about. In the election of 1790 the Republicans of Pennsylvania backed Arthur St. Clair [an Original Member of the Society] for Governor, but in the event Mifflin carried the State by an overwhelming majority to become Pennsylvania’s first elected Governor. He remained in office until 1799, three full terms, the maximum allowed by the new Constitution.

During all this time, Mifflin showed a growing sympathy with Jeffersonianism, which was to set the tone of Pennsylvania politics and of the nation for a generation. It was probably this sentiment that dictated Mifflin’s initial resistance to Federal intervention during the crisis of the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. In spite of Mifflin’s exercise of convoluted legalisms to inconvenience Washington’s and Hamilton’s efforts he finally was made to see the necessity for summoning the Pennsylvania Militia in support of the military arriving from neighboring states. Even then Pennsylvania did not furnish her quota of militiamen, but Mifflin did at least accompany his troops west.

Mifflin’s final term as Governor from 1796 to 1799 was marked by evidently failing powers. He was frequently ill and the government was virtually in the hands of Alexander James Dallas, Secretary of the Commonwealth. Old accusations against his integrity reappeared and new ones surfaced, in particular that he was a drunkard. In regard to Mifflin’s last years that Benjamin Rush said, “Had he fallen in battle, or died in the year 1778, he would have ranked with Warren and the first patriots of the Revolution.” And, “His popularity was acquired by the basest acts of familiarity with the meanest of people.”

At the end of his last term as Governor Mifflin was returned to the General Assembly in the election of 1799. In April he signed the bill removing the state capital from Philadelphia to Lancaster, and it was to Lancaster that he traveled to take his seat on 20 December. On Monday morning, 20 January 1800, Thomas Mifflin died. He was buried in the churchyard of the German Lutheran Church of Lancaster at the expense of the Commonwealth. It was said then and since that he was penniless.

On 4 March 1767 Thomas Mifflin had married at Fair Hill Friends’ Meeting, Sarah, daughter of Morris and Elizabeth (Mifflin) Morris, his cousin. She was born 5 June 1747 and died in Philadelphia 1 August 1790. The joint portrait of Thomas and Sarah Mifflin by John Singleton Copley, now at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, is one of the glories of American colonial painting. Contemporaries of Mrs. Mifflin found her handsome, praiseworthy and amiable. There were no children of this marriage. Jacob Hiltzheimer (1729-1798) of Philadelphia was a close friend and associate of Thomas Mifflin, and his diaries have furnished many insights into the domestic and political life of his times. Hiltzheimer frequently referred to “the Governor, his two daughters”, “the Governor’s daughter Fanny”, “the Governor with his daughter Emily”, and similar expressions. This anomaly will explain such contemporary expressions as that of a newspaper adversary, “Federalist”: “the cravings of sensual appetites were indulged at the expense of the moral duties of the man”, and those of another enemy, Benjamin Rush, “Our Governor has realized all the fears of the friends of virtue in the state. It is hard to tell whether his private immoralities or public follies expose him to the most contempt.”

Thomas Mifflin of the “Falls of Schuylkill”, Philadelphia County, made his will on 29 November 1797 and it was probated on 25 January 1800. His heirs were the children of Emily, the wife of Joseph Hopkinson; the two children of Frances, wife of Jonathan Mifflin; Marie LaGrange and Thomas Brown LaGrange of the State of New York; Mifflin’s sister-in-law Susannah Morris; his nephew Thomas; and his niece Elizabeth Mifflin.