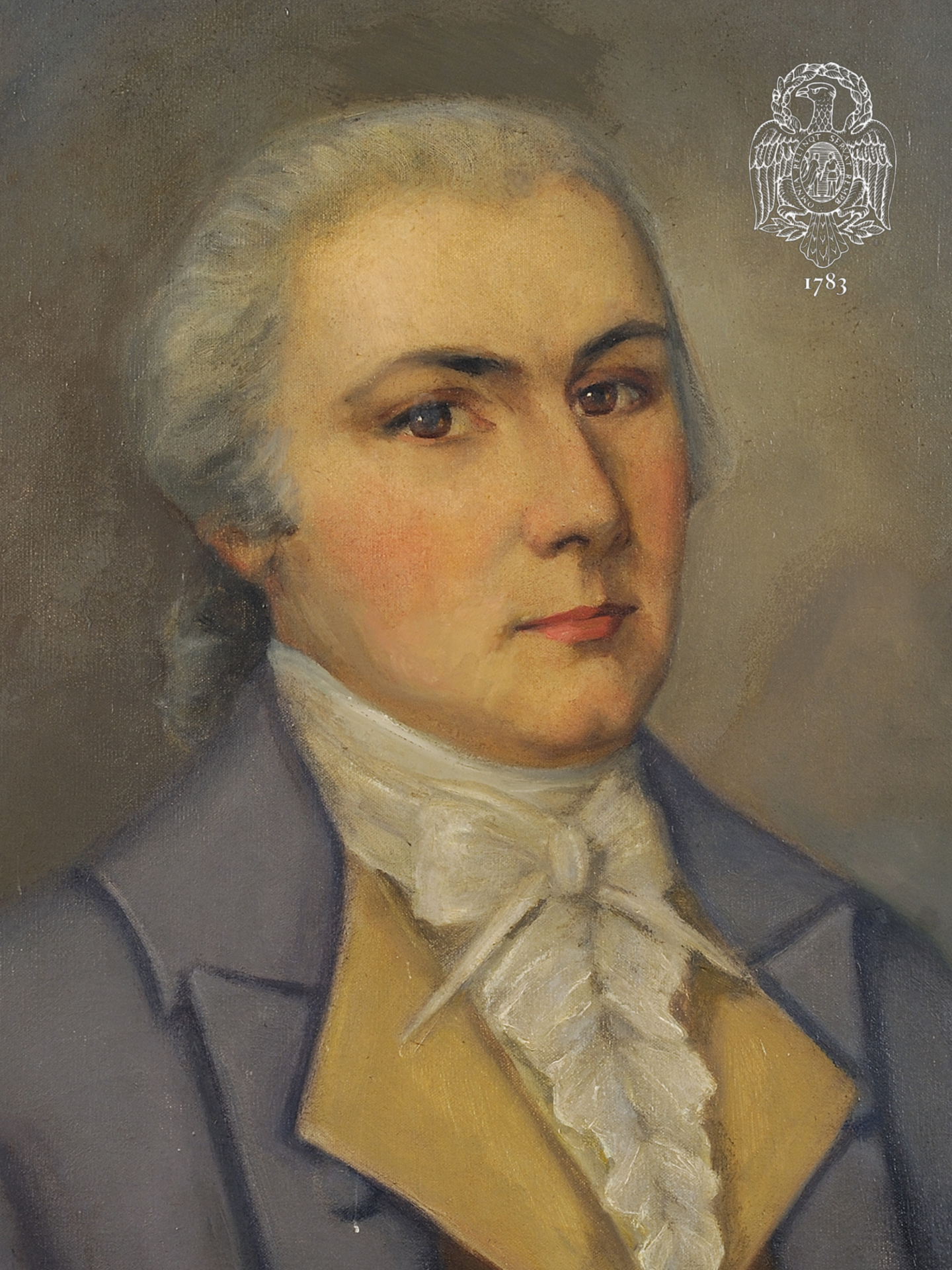

Maj. James Randolph Reid

James R. Reid, a son of James and Margaret Reid, was born on what was then thought to be the Manor of Maske, Hamiltonban Township, York (now Adams) County, on 11 August 1750. His father came there in August 1738 as one of the earliest settlers, and on 26 June 1767 he received a warrant for nine hundred acres, called “Letterkenny”, one of the largest individual grants in the area.

Reid was more highly educated than most of the Pennsylvania officers: he graduated from Princeton, A.B., in 1775 and received an A.M. in 1780 while still in service. At college Reid was a member of the American Whig Society which fostered many a revolutionist. On 6 January 1776 he was commissioned First Lieutenant of Captain Thomas Church’s company of riflemen in Anthony Waynes’s Fourth Pennsylvania Battalion, authorized only the preceding December. His company moved to join the Americans in Canada by way of New York and Albany, and first saw action at Trois Rivières on 8 June 1776. As the Americans retreated from Canada this battalion was of the rear guard, moving first to Crown Point and finally to Ticonderoga in July. There Colonel Moses Hazen of the Second Canadian Regiment was court-martialled and exonerated on charges brought by Benedict Arnold for actions in Canada. Reid’s battalion formed part of the garrison at Ticonderoga during that difficult winter; and on 3 November 1776 he was commissioned Captain in Colonel Hazen’s regiment, “Congress’ Own.”

Much has already been said in this study concerning the operations of Hazen’s Regiment, but a study of Reid’s history must include at least an overview of the unfortunate feud that developed between Hazen and Reid which must have been, at the least, disruptive for the entire organization and fatal to its morale. At best only a “truce” existed between American officers in the regiment and the French-Canadians, who not only spoke a foreign and largely incomprehensible language but were also Papists. Public disagreements among its top officers could in no sense have contributed to its well-being and efficiency. All started well, however: the regiment took part in Sullivan’s raid on Staten Island on 22 August 1777, and fought efficiently in the early battles of Long Island (27 August 1776), Brandywine (11 September 1777) and Germantown (4 October 1777). On 1 September 1777 Reid was promoted to Major, an indication of Hazen’s confidence in him.

The regiment spent the winter at Valley Forge, and during most of 1778 Hazen was concerning with planning a new but abortive invasion of Canada, while his regiment was at Albany. From there it moved to the Highlands, near White Plains, New York, but the Canadian venture was never forgotten and Hazen’s thoughts turned to the construction of a military road through the Vermont wilderness for the transportation of men and supplies. His planning was still alive when the regiment was ordered into winter quarters near Danbury, Connecticut, in November. In the Spring of the new year Hazen was gratified by being ordered to begin work on his military road, and during the summer of 1779 the stubborn and hardy soldier pushed and fortified it to “Hazen’s Notch” almost at the Canadian border. He might have gone farther but in August he was ordered back to Peekskill by Washington.

On 13 March 1779 Congress adopted a resolution stating that “all officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers, now belonging to the corps of light dragoons, and artillery and infantry, and the corps of artillery artificers, commissioned and inlisted since the 16 of September 1776,…be considered as parts of the quotas of the several States…”. This was designed to place on the state of origin the responsibility for supplying and paying soldiers of organizations, such as Hazen’s, belonging to no state Line. The wording was defective and vague as Knox pointed out to Washington in a letter of 6 April 1779.

Hazen’s Pennsylvania officers met with no success in obtaining supplies from either Congress or the State: the resolution did not name their regiment specifically. From Peekskill on 30 November Hazen wrote Washington a long report of the condition of the regiment, recapitulating its history and needs. The letter furnishes good evidence of Hazen’s concern for the well-being of the men for whom he was responsible, and he went on to make a number of proposals for obtaining both supplies and money for his men. In December Hazen’s Regiment was assigned to Edward Hand’s [an Original Member of the Society] Brigade and moved to Morristown for the winter. Here Hazen’s Pennsylvanians observed for themselves the provision made for officers from the New England states with whom they were brigaded, and they recalled the resolution of 13 March. On 14 December Major Reid, Captains James Heron, Thomas Pry and James Duncan, Lieutenant William Stuart, and Ensigns Andrew Lee and Lawrence Manning, all of Pennsylvania, petitioned President Joseph Reed that they be recognized and supplied, saying,

…we were taught to believe we could render as much service as in any other Corps, and by no means expected to be considered as aliens, or excluded any benefit common to the officers of the same State….the advance[d] price of every necessity will not leave it in our power to continue in a Service in which we are so much more interested, unless some provision shall shortly be made for us….

On 29 December the Supreme Executive Council “Resolved, That the Gentlemen be informed that their request cannot be complied with, until this Board are authorised so to do by the House of Assembly.” Reid had gone to Philadelphia, no doubt to hand-deliver and lobby for this memorial; on 11 February 1780 Hazen wrote President Joseph Reed,

Major Reid,…has acquainted me with his application to your Excellency for supplies of cloathing, &c., for a few officers of the Pennsylvania State,…I do not sensure his application, because I am persuaded he was prompted to it by motives of mere Necessity; however hard his case, yet there are many other officers in the Regiment who are equally situated, and that are not entitled to any Redress…I think it now a part of my Duty at this time to oppose any Partial provision for Officers or men in [the regiment]…

President Reed had informed Washington of the matter and the latter on 23 February 1780 replied rather non-committedly, but on 28 February the Council resolved that Hazen’s Pennsylvania officers were to receive the same treatment given all the other officers of the Line, but it required yet another directive to the Clothiers before they would comply. The crisis was reached on 20 September 1780 when Reid and eleven other American officers of Hazen’s regiment addressed a memorial about their grievances directly to Washington. The officers felt they had been patient long enough, that they were in great need, and that Hazen was partial to his fellow-Canadians. The memorial specified that they were denied promotions, that Hazen refused to consider their problems, and, in short, that they were discriminated against in every way. The officers wished to have the regiment either attached to some state Line, or that it be dissolved and the personnel sent to their respective states. Hazen felt, correctly, that his officers, led by one of his own majors, had gone out of channels and over his head without mentioning or discussing matters with him beforehand. The Memorial was a masterpiece of bad timing: on 25 September Arnold’s treason was uncovered and all military minds turned toward that incipient catastrophe. This was of more than casual importance to Hazen, whose allegiance to the Continentals was questioned more than once: Major André himself had mentioned him as one who could be “had”.

Between Reid and Hazen things went from bad to worse. Reid now charged his Colonel with financial fraud, submitting false musters and returns, and with ungentleman- and unofficer-like conduct in selling army rum for his own profit. While these charges were being investigated, Reid at West Point sat on the boards of inquiry that inevitably followed the Arnold treason. But at a court-martial in November 1780 Hazen was exonerated of all charges. Hazen then had Reid arrested, charging him with disobedience of orders, embezzlement, and conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman. Reid was confined during his arrest, and in turn he charged Hazen with delaying his trial in order to punish him thereby. Unfortunately, in trying to justify himself Reid alienated many of his fellow officers who felt he unfairly cast aspersions on them; this came back to haunt Reid later. Hazen’s charges went to court-martial in December, and because of delays and adjournments did not conclude until February 1781. Reid was found innocent of embezzlement, but the court recommended that he be reprimanded by Washington, which was done. Reid remained in the regiment and incendiarism was avoided by sending him to command a part of Hazen’s brigade away from the Colonel’s area.

In August 1781 Washington began the great move toward Virginia that still seems such a tactical marvel. At Yorktown Hazen commanded the Second Brigade of Lafayette’s Division, called the “Light Infantry”, in which the Canadian Regiment was under the command of Lt. Colonel Edward Antill. By that time the Reid-Hazen feud had so definitively divided the loyalties of the regiment’s officers that some declared that they would act under Major Reid’s orders only for the good of the country. Reid retained his post, and Lafayette saw that his Division was in the thick of the fighting. When the regiment returned north it was sent to Lancaster on prison-guard, and Reid was given leave, on condition that he return in good time so that Hazen and other officers could in turn be relieved. Reid did not return on time, and when he did return in May he was arrested by Hazen.

The charges were again “disobedience of orders, unmilitary conduct and ungentleman and unofficer-like behavior”, and this time, with Hazen’s connivance, the charges were levelled by some of his fellow-officers. Refusing to resign or transfer, Reid went to trial at West Point in December 1781 and was acquitted. Hazen then accused the Judge Advocate, Lieutenant Thomas Edwards of Massachusetts, of incompetently directing the trial, and of basic flaws in the court-martial system. Washington appointed a Board of Inquiry which vindicated Edwards, and that finding and the result of Reid’s most recent court-martial were published to the Army. Hazen and his officers, still not satisfied, demanded that Reid justify in a public hearing his 1780 assertions that the regiment’s officers were lax and dishonest. A new Court of Inquiry met at West Point in May 1782, to be non-plussed by Reid’s questioning their competence to inquire into his court-martial of two years previously and his refusal to produce the evidences on which he had based his statements. In short, he refused to attend. Washington ordered the court to proceed, render a decision and put an end to the unseemly scandal. The court finally found no reason to justify Reid’s charges: to Washington that ended the matter. Hazen and his officers were not satisfied with this and besieged Washington with petitions. Hazen again ordered Reid arrested, and this Reid ignored.

The long-suffering Commander-in-Chief asked his general officers whether all proper steps had been taken to satisfy Hazen and the aggrieved officers; if not, what else should be done; and whether Reid should be arrested and brought to yet another trial. The generals said “yes”, all proper steps had been taken, and “no”, Reid should not again be arrested. Washington concluded that this ended the matter, while Hazen displayed a tendency to pursue the affair. Washington wrote him in June 1783 “you will consider this as finishing an affair that has given so much trouble to the Army.” In any case, at about that time both Hazen and Reid left the Army and matters did indeed come to an end.

Reid signed the “Parchment Roll” of the Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania as “Major H Regt”: he could not bring himself to write out the hated name; he signed also the “Pay Order of 1784”.

Virtually nothing has been found concerning Reid’s activities for the next three years, and it may have been then that he was married. On 13 November 1787 he was elected from Cumberland County to the expiring Continental Congress, in which he served as a conservative member until 1789. His colleagues from Pennsylvania were James Armstrong, Jr., William Irvine, [ Original Members of the Society], William Bingham, Tench Coxe, and Samuel Meredith. Reid arrived in New York on 19 December 1787 and on 7 July 1788 he and William Bingham offered on behalf of Pennsylvania “¼ of a Doll. P[er] Acre” for the land in what was to be known as the “Erie Triangle”. Reid’s other concerns included the permanent location of the national capital, which he naturally hoped would be in Pennsylvania, and the establishment of a military force to patrol and police the developing West. He applied to serve there without pay but with no success. In January 1789 Reid, writing from New York, described himself to Nicholas Gilman of New Hampshire as having “given ten years of life to the Country”, that his “circumstances [were] independent, and that he had the “leisure to attend to public business”. He hoped to be given the post as collector of federal revenue in Pennsylvania. Gilman received this letter in February, but about the time it was written Reid had started for Carlisle, seriously ill. He died at “Middlesex”, Cumberland County, on 25 January 1789, leaving no issue.

According to family records which there is no reason to doubt, but for which no documentation has been found in this study, James R. Reid married as her second husband, Frances Gibson Callender, the widow of Robert Callender, Indian trader of Cumberland County, who had died in 1776. The marriage allied Reid to an interesting network of pioneers, Indian traders and soldiers of central Pennsylvania. Frances Gibson was the daughter of George Gibson and his wife Elizabeth de Vinez of Lancaster County; her brothers were John (1740-1822) and George (1747-1791) Gibson. Both had important, not to say romantic, careers, too lengthy to recount here. It must be sufficient to say that George was involved in important military affairs both in colonial and revolutionary America and died 14 December 1791 as a result of injuries received while serving in General St. Clair’s ill-fated campaign in the Old Northwest. By his wife Ann West Heorge Gibson was the father of John Bannister Gibson, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. John Gibson had similar frontier service, held a Virginia commission in the Continental Army, commanded at Fort Pitt, and was an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia.

Frances Gibson Callender’s step-children were Ann, the wife of General William Irvine [an Original Member of the Society]; Elizabeth, wife of Dr. John Andrews, Provost of the University of Pennsylvania; and Isabella, wife of William Neill, merchant of Baltimore. Frances’ own children by Robert Callender were Robert, who married Harriet, the daughter of Colonel William Butler [an Original Member of the Society]; Martha, the wife of the Hon. Thomas Duncan, Judge of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ; Mary, the wife of George Thompson, son of Colonel William Thompson of the Pennsylvania Rifle Battalion ; and two other daughters.

Reid’s death had occurred at “Middlesex”, the estate of Robert Callender, where without doubt his widow resided. Middlesex Township, Cumberland County, was named for the estate, and in 1791 the place was acquired by Colonel Ephraim Blaine [an Original Member of the Society]. Whether Reid there wrote his long and interesting will is unknown for it is undated; he was “sorely afflicted with pain.” His chief beneficiary was his wife Frances, and he bequeathed more than two thousand acres of land in Pennsylvania and Kentucky, as well as two tracts of the “Purchase of 1784” in “William Powers [an Original Member of the Society] district”. Most bequests were to nieces and nephews: he named his father James, and his own brothers (making certain his identification with the native of Hamiltonban Township). The strongest circumstantial evidence of his marriage to Robert Callender’s widow is Reid’s reference to “my beloved son, Robert Callender”, who was given Reid’s riding horse, saddle and bridle. Perhaps the most interesting bequest was Reid’s Thirteenth: “I devise to my friend Thomas Shippen, the son of Doctor William Shippen, my Eagle in hopes that the Society of the Cincinnati will admit as a member a man who has done so much honor to his country.” In spite of Reid’s hopes Thomas shippen did not become a member of the Society of the Cincinnati. In 1790 Frances Reed [sic] was enumerated as a resident of the “Eastern Portion” of Cumberland County, with one male over the age of sixteen, three females, three other free persons and four slaves.