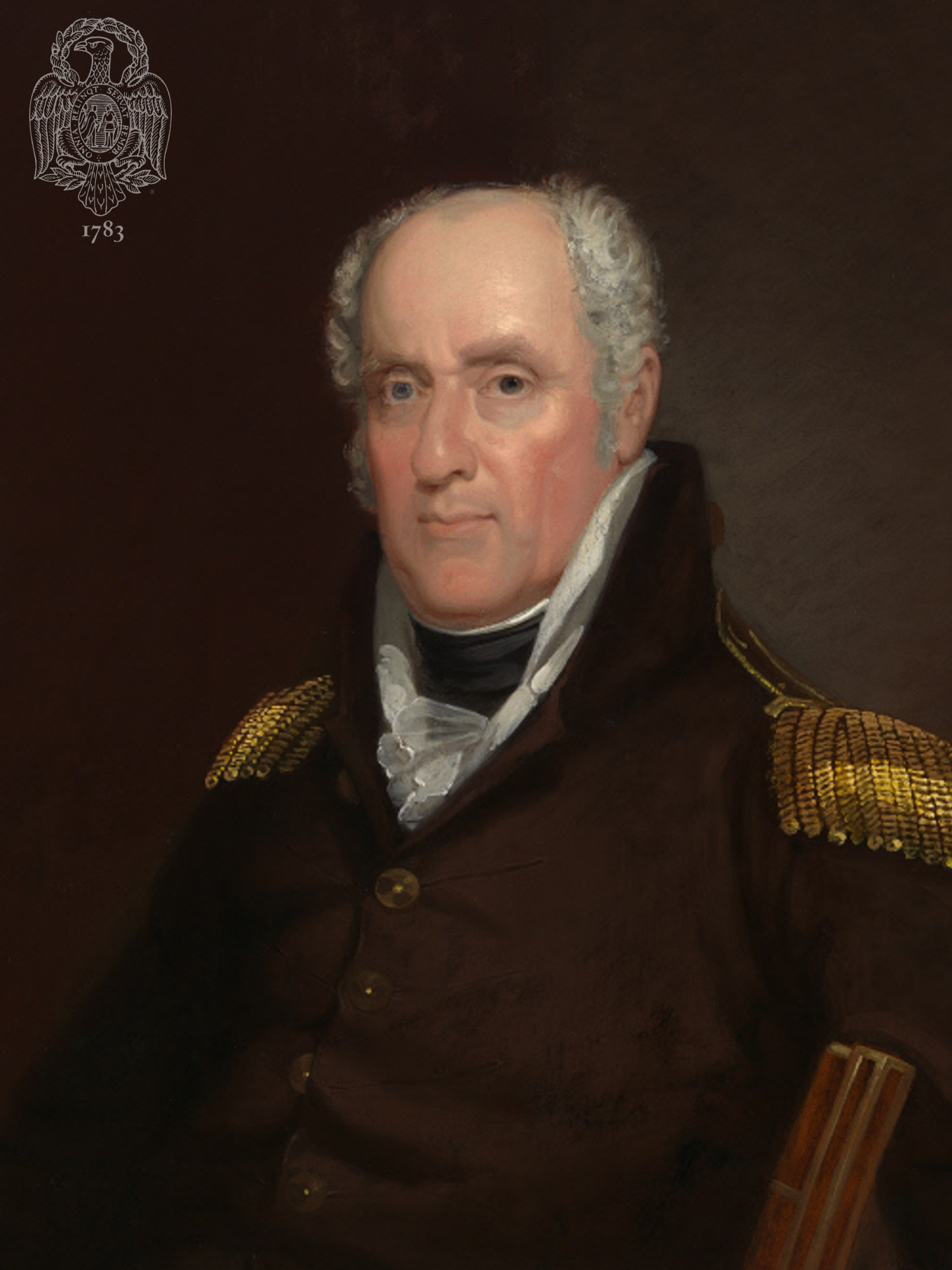

Maj. John Armstrong, Jr.

Major John Armstrong was the son of Brigadier General John Armstrong of Carlisle (1717-1795), born in Ireland, with a distinguished military career on the American frontier during the French and Indian War. Although a Continental Brigadier General, the elder Armstrong resigned his rank in 1777 to become a Major General of the Pennsylvania Militia until the end of the war. He was a member of the Continental Congress and a trustee of Dickinson College.

The younger Armstrong was born 25 November 1758 at Carlisle, his father having married Rebecca (Armstrong) Lyon. At the outbreak of the Revolution he was a student at Princeton but left the college and was with the ill-fated Canadian Expedition in 1775. A Captain of the Pennsylvania Militia, be left the staff of General James Potter to become aide de camp to General Hugh Mercer, who promoted him Major. Both men were wounded at the battle of Princeton and Mercer died two days afterwards. In a short time Armstrong became aide to Horatio Gates and remained as such until 1780. When Gates became commander in the Southern Department, Armstrong was made Adjutant of the Southern Army. After Gates’ disaster at Camden in August 1780 he returned north, Armstrong with him, and they remained together in the Hudson Valley for the rest of the war.

Armstrong has long been acknowledged as the author of the “Newburgh Letters” of 1783, recognized by Washington as subversive of the ideals and principles of the Revolution, and determinedly squelched by him in March 1783. He became Secretary to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania later that year, and in 1784 as Colonel of the Pennsylvania Militia was sent to the Wyoming Valley in the hopes of pacifying the escalating violence between the Connecticut and the Pennsylvania settlers there. His efforts were not successful: he was too unyielding towards the “Yankees” and too committed to “Pennamite” speculative interests. Armstrong was certainly looked upon as unreliable by his Federalists compeers: although selected to attend the Annapolis Convention in 1786 he did not attend; again, chosen as one of three judges for the Northwest Territory in 1787 he did not accept; he was considered but not selected to represent Pennsylvania at the Federal Constitutional Convention the same year. On the other hand, he was elected to the Continental Congress in March 1787, and reelected in November 1788.

On 19 January 1789 Armstrong married Alida Livingston, daughter of Judge Robert Livingston of “Clermont”, New York, the sister of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, thereby becoming allied to one of the most powerful New York families of both the Colonial and Federal periods. Armstrong thus became brother in law to Colonel Henry Beekman Livingston, General Richard Montgomery and Colonel Morgan Lewis. His wife was also cousin to Lt. Colonel Henry Brockholst Livingston, to Mrs. William Alexander (“Lord Stirling), and to Philip Livingston, Signer of the Declaration of Independence. This marriage united Armstrong to the political fortunes of the Livingston family, but he often showed himself not unwilling to follow another course if he thought it to his advantage to do so. Armstrong was briefly connected with Washington Lodge Number 59, Freemasons of Pennsylvania, having been initiated on 9 September 1796, but his name was withdrawn the next day, possibly because of his removing to Dutchess County, which he did after his marriage. When Robert R. Livingston retired as Minister to France in 1804 he was able to have Armstrong named in his place. Armstrong remained as Minister until 1810, actively promoting the United States’ interests in the Florida negotiations with Spain, and, with Napoleon, difficulties about the Berlin and Milan Decrees. He was convinced that Napoleon accepted Americans’ concerns regarding the latter, and accepted obligations on the part of the United States that generated a hostile and unsparing attitude towards England which culminated in the War of 1812.

Although Armstrong appears to have considered running for Vice President of the United States in 1812, he instead accepted a commission as Brigadier General in July and was placed in command of the defences of New York. His success there induced James Madison to name him Secretary of War in February 1813. In this job Armstrong’s background, experience, and dominating personality were successful in making him an initial success. He recognized the abilities of Andrew Jackson, Winfield Scott and Jacob Brown. “He did his best to protect the army supply system against favoritism and corruption, and supported efforts to recruit black soldiers over southern objections.” Armstrong, however, clashed bitterly with both Madison and Monroe, probably because of his ambitious plans to become President. Before his plans could mature the burning of the city of Washington in August 1814 put an end to them and he resigned from the Cabinet in September.

Thereafter Armstrong had perforce to play the role of the country squire, for which he was fitted both temperamentally and financially. He never abandoned his avocation as pamphleteer which he had assumed in 1783, and his Notes on the War of 1812 was designed to justify and exonerate his career. His projected history of the Revolution was destroyed by a fire that badly damaged “La Bergerie”, his home. In his last years, Armstrong deserted his Presbyterian heritage, and he became a communicant of the Episcopal Church in 1842. On 1 April 1843 he died at his home and was buried in the Armstrong mausoleum at Red Hook, New York. He was survived by five sons and one daughter.